OK. Take a deep breath:

Healthcare

First, the opinion in its entirety.

And explained in one paragraph, from the Atlantic: The Affordable Care Act, including its individual mandate that virtually all Americans buy health insurance, is constitutional. There were not five votes to uphold it on the ground that Congress could use its power to regulate commerce between the states to require everyone to buy health insurance. However, five Justices agreed that the penalty that someone must pay if he refuses to buy insurance is a kind of tax that Congress can impose using its taxing power. That is all that matters. Because the mandate survives, the Court did not need to decide what other parts of the statute were constitutional, except for a provision that required states to comply with new eligibility requirements for Medicaid or risk losing their funding. On that question, the Court held that the provision is constitutional as long as states would only lose new funds if they didn't comply with the new requirements, rather than all of their funding.

Slate has an estimated 4,127 articles up on yesterdays ACA decision. Fortunately, it has them all linked from this one helpful page.

Adam Liptak at the Times praises Roberts deft political hand.

So does Ezra Klein at the Washington Post.

Others report that states might have a tough time meeting ACA deadlines.

At Salon, Bernstein says this means it's time for liberals to stop saying the Court needs "fixing."

But Paul Campus says this is evidence of a broken system.

And Andrew Koppelman argues that Kennedy joined the radicals.

Robert Reich's take.

Alex Seitz-Waltz wonders if it was, in fact, a conservative victory.

Joan Walsh weighs in on the "BFD".

Even the Chronicle of Higher Education gets in on the game, telling us that medical students and teaching hospitals applaud the Court's decision.

Michele Goodwin (also at the Chronicle) says Roberts interrupted politics as usual, but that hard questions remain.

At The Atlantic, Daniel Epps says Roberts scored a coux a al Marbury v Madison.

The Atlantic also gives us a handy guide to the spin on the ACA.

Other Stuff that ALSO Happened

The New York Times reports on the Court's decision to strike down the Stolen Valor Act. (And here's an old Slate piece explaining the case.)

The House held AG Eric Holder in contempt.

The Atlantic reports the same.

Jack Balkin, Walter Dellinger, Dahlia Lithwick, and Judge Richard Posner exchange emails on the state of the law and the constitution. (Note: Posner is about two emails from being challenged to a dual by Scalia)

Eric Posner on the SCOTUS ruling in Arizona.

Salon also weighs in on that decision.

Michael Myerson writes about the constitution and the protection of religious freedom.

Salon wonders why Republicans in Iowa aren't making a bigger deal out of gay marriage.

And why old conservatives are dying to tell you that they love Bruce Springsteen.

Friday, June 29, 2012

Thursday, June 28, 2012

Special Round-Up: ACA Upheld

For the thousands of people who rely on this blog for legal news, I... what? no one does? Oh. Well, anyway, you may have heard that a fairly important decision came down today. Chief Justice Roberts joined the liberal wing of the Court in upholding the ACA more or less in its entirety (including the hot button individual mandate). I'll devote an entire section of links on this in tomorrow's round-up, but a few to get the ball rolling:

The opinion, in its entirety.

The New York Times piece on the decision.

And some NYT speculation on the decision's electoral effects.

The Atlantic on what the decision means.

And on what's next for Obama and Romney as a result.

And for fun, a 2007 piece on Chief Justice Roberts.

Slate's continuing coverage.

Salon's take.

The opinion, in its entirety.

The New York Times piece on the decision.

And some NYT speculation on the decision's electoral effects.

The Atlantic on what the decision means.

And on what's next for Obama and Romney as a result.

And for fun, a 2007 piece on Chief Justice Roberts.

Slate's continuing coverage.

Salon's take.

Monday, June 25, 2012

You Can't Have it All, After All

At least in the professional worlds of political science and public law, two maelstroms erupted this week. Sunday's New York Times includes an editorial by a Northwestern professor who more or less calls out the whole field as a drain on the NSFs resources, and perhaps just bad at their jobs. I don't think it's particularly coherent - and certainly not convincing - but others have done a much better job taking it apart than I could: check, for example, the coverage given at The Monkey Cage.

The other happening is that every singe woman I know posted the Atlantic article by Anne-Marie Slaughter. (OK: maybe it just FELT like every woman I know. It might have been fewer.) Before I send anyone screaming from their computer or writing angry comments on this post, I'll say that the piece is excellent and that Slaughter does a tremendous job picking apart the difficulties that face my generation's women as they try to navigate the socially very complicated tradeoffs between career and family. But I do have a couple of questions/queries/criticisms about the piece.

I have three, to be specific. The first is that the tradeoffs Slaughter points out apply to men as well as women. Much to her credit, Slaughter recognizes this and does a great job highlighting some of the social norms that make the choice to choose career over family seemingly easier (or at least more knee-jerk) for men. Nor does Slaughter claim that the economic and societal structures that make the choice more socially problematic for women cannot apply to men as well. Here, I just want to highlight that a man who values family life and children faces similar constraints. Most men work jobs that require a huge number of hours, and that necessarily makes it more difficult to spend time with their kids. Simply because they tend not to be as reflective on this dilemma - or to feel like "bad feminists" when they choose one over the other - doesn't mean it ensnares them any less.

This speaks to a second, broader question: why does anyone assume we are entitled to "have it all?" Slaughter presents the obstacles to having a social life AND family life AND professional life, but seems not to consider the possibility that life sometimes simply requires us to make sacrifices. I admire the ambition behind the sentiment - and there's a degree to which I share it - but I wonder if its attempts to eliminate the idea that we might have to make choices is ultimately harmful. Slaughter is right to point out that our societal values work against a balanced life, but there are aspects of this that aren't malleable. A few propositions: 1) we are always going to want experts to be, you know, really good at what they do; 2) this requires experts to spend a lot of time doing something, and in competitive positions it requires them most often to spend more time than other people, 3) as a result, something of an intellectual arms race for exalted positions seems inevitable. If I'm about to have brain surgery, I want one of the best brain surgeons around to do it, and I probably couldn't care less about that person's work/family balance.

It isn't just that we undervalue family life - though I think we do, especially for men - it's that the logic behind being the best at anything often requires an enormous amount of time spent on that one thing. Slaughter is undoubtedly right that being "time-macho" is prevalent, and probably counterproductive, but this hides the simple fact that being really good at something takes a lot of time. Being good enough at basketball to play in the NBA, or at medicine to be a cardio-thoracic surgeon, or at law to be the Dean of the Wilson School at Princeton, requires an enormous number of hours of practice, which have to come at the expense of something because there are a finite number of hours in a day, days in a week, weeks in a year, years in a lifetime. If you had a friend who said he didn't want to have to choose between two careers - say film directing and being a high-powered lawyer - you would almost certainly remind him that both of those require a high degree of time and expertise, and that it will be difficult or impossible for him to do both. He has to make a choice, a sacrifice. Why would we expect other life choices to be any different? If "having it all" means getting to do everything you want with your life without having to make choices or sacrifices, then no one can have it all, man or woman, because we do have to make hard choices about our lives.

Let me illustrate part of this with my third, narrower point. Slaughter says that we ought not to privilege parents over other workers - which I think is right - and that because women tend to be the primary caregivers, being a parent most often places the burdens of extra work on them rather than equally on both partners. In a two career family, this makes it harder for the woman than for the man. No argument with either of these points so far as I am concerned. But a parable from Slaughter's time at Princeton makes me question how committed she is to the notion that we don't or ought not to privilege parents. She notes that any tenure-track faculty member - male or female - who has a child while at Princeton automatically gets a year added to the tenure clock. I think a lot of us - myself included - reflexively say "that's great!" But why?

My roommate - who really ought to get joint author credit for this post since I'm stealing a lot of his points - made me question why I unflinchingly assumed that new parents ought to get that extra year. Now, there are reasons like "so they can spend more time with their kids" that are obvious, but his critique runs deeper. By enabling new parents to both spend time with their kids and get tenure, we are implicitly saying "having a child is not a choice that should interfere with your career prospects." Again, I think a lot of us say "how great" without actually reflecting on this that much. WHY do we feel that having a child is a choice that shouldn't require that kind of sacrifice? There might be some very good reasons for this; I haven't thought about it enough to say for sure what some of them may or may not be. The point is that we don't feel the need even to articulate such reasons.

Consider the following four scenarios:

1) I put work on the back burner for a year because I just had a child.

2) I put work on the back burner for a year because one of my parents is sick and I move back home to help out around the house.

3) I put work on the back burner for a year because I don't have time to read the classics as avidly as I would like, and I think that I will be a better person and a better academic if I take a year to read and reflect on the classics of world literature (which is, I think, a perfectly colorable argument, by the way).

4) I put work on the back burner for a year because I haven't travelled that much and I think I will be a better person, a more reflective academic, and better cosmopolitan citizen of the world if I visit all seven continents and learn more about cultures in other places.

Each of these represents a life choice a person could very reasonably make to enjoy their life more, enrich their views of the world, nurture familial relationships, be a better person, etc., etc. But the rule that Slaughter finds so much value in at Princeton decides that only one of these choices is one that shouldn't have to interfere with your career (maybe #2 as well, depending on the workplace; but good luck getting your tenure clock in Biology extended to read the complete works of Dante, Cervantes, and Shakespeare, no matter how great a person that might make you). If I end up as a single academic without children, none of the choices I can make to enrich my life at the expense of my work will be one that my university compensates for by ameliorating the negative effects on my career.

Again - I really can't emphasize this enough - we might, on reflection, decide that there are really good reasons to minimize the effect having children has on new parents. If nothing else, people are going to have children, they simply are, no matter how the purported cost/benefit balance is structured. As an old professor of mine put it, "if people thought rationally about having children, no one would ever have any." Given this social/biological fact and its prevalence, we might say that we want to ensure that people can be good parents without abandoning other pursuits. The point, though, is that we don't reflect on it. We tacitly assume that having children is a choice that ought to impact your career as little as possible when we can help it. Why do we assume this? This isn't a rhetorical question meant to imply that we shouldn't; I'm seriously asking what the underlying reasons are. They may require some examination.

Slaughter does such a great job emphasizing the background social norms and default assumptions that make the choices we have to make more problematic for women that it makes it all the more surprising when she doesn't examine nearly as critically the fact that we do privilege married couples and parents at the expense of single people (tax breaks for married couples, for children, leaves of absence or extensions for having kids, etc., etc.; those dollars come from single people, too), even as she says we shouldn't. Especially when the people who make the rules about these things tend to be married people with children, oughtn't we at least look critically at the self-authored rules that privilege their position?

At root, I don't have any real problems with the arguments Slaughter makes, but with the unexamined assumptions that hide behind them. WHY do we feel that we ought to be able to "have it all" without having to make hard choices and sacrifices? WHY do we think that having children is the sort of choice that shouldn't impact your career? Do we have good reasons for these baseline assumptions? And, if not, how does that impact Slaughter's related arguments?

Rules like the one Slaughter favors matter precisely because they privilege one choice (and people who make it) without necessarily encouraging reflection on those privileges and why they are or are not justified. This gets especially dangerous and prickly when we think of something as "natural." Now, I'm pretty sure that procreating is about as natural an activity as we're likely to find, but doing it in marital pairs is subject to (and the result of) all sorts of social norms and pressures (doing it in biological pairs was utterly unavoidable until about thirty years ago). But it's the very description of something as "natural" that encourages us to take it as a given and stop reflecting on how we build our social rules around it.

At root, I'm just encouraging everyone to A) read Slaughter's piece if you haven't already, it's great, but B) consider whether Slaughter's fantasy world without hard life choices is one that can ever exist, and C) critically reflect on the position we place childbearing and rearing in in our political and social spaces, and why we have rules that privilege that choice at the expense of others.

Comments, counterarguments, and the good points I inevitably missed are always welcome, but even more so today, when I have questions that aren't remotely rhetorical.

The other happening is that every singe woman I know posted the Atlantic article by Anne-Marie Slaughter. (OK: maybe it just FELT like every woman I know. It might have been fewer.) Before I send anyone screaming from their computer or writing angry comments on this post, I'll say that the piece is excellent and that Slaughter does a tremendous job picking apart the difficulties that face my generation's women as they try to navigate the socially very complicated tradeoffs between career and family. But I do have a couple of questions/queries/criticisms about the piece.

I have three, to be specific. The first is that the tradeoffs Slaughter points out apply to men as well as women. Much to her credit, Slaughter recognizes this and does a great job highlighting some of the social norms that make the choice to choose career over family seemingly easier (or at least more knee-jerk) for men. Nor does Slaughter claim that the economic and societal structures that make the choice more socially problematic for women cannot apply to men as well. Here, I just want to highlight that a man who values family life and children faces similar constraints. Most men work jobs that require a huge number of hours, and that necessarily makes it more difficult to spend time with their kids. Simply because they tend not to be as reflective on this dilemma - or to feel like "bad feminists" when they choose one over the other - doesn't mean it ensnares them any less.

This speaks to a second, broader question: why does anyone assume we are entitled to "have it all?" Slaughter presents the obstacles to having a social life AND family life AND professional life, but seems not to consider the possibility that life sometimes simply requires us to make sacrifices. I admire the ambition behind the sentiment - and there's a degree to which I share it - but I wonder if its attempts to eliminate the idea that we might have to make choices is ultimately harmful. Slaughter is right to point out that our societal values work against a balanced life, but there are aspects of this that aren't malleable. A few propositions: 1) we are always going to want experts to be, you know, really good at what they do; 2) this requires experts to spend a lot of time doing something, and in competitive positions it requires them most often to spend more time than other people, 3) as a result, something of an intellectual arms race for exalted positions seems inevitable. If I'm about to have brain surgery, I want one of the best brain surgeons around to do it, and I probably couldn't care less about that person's work/family balance.

It isn't just that we undervalue family life - though I think we do, especially for men - it's that the logic behind being the best at anything often requires an enormous amount of time spent on that one thing. Slaughter is undoubtedly right that being "time-macho" is prevalent, and probably counterproductive, but this hides the simple fact that being really good at something takes a lot of time. Being good enough at basketball to play in the NBA, or at medicine to be a cardio-thoracic surgeon, or at law to be the Dean of the Wilson School at Princeton, requires an enormous number of hours of practice, which have to come at the expense of something because there are a finite number of hours in a day, days in a week, weeks in a year, years in a lifetime. If you had a friend who said he didn't want to have to choose between two careers - say film directing and being a high-powered lawyer - you would almost certainly remind him that both of those require a high degree of time and expertise, and that it will be difficult or impossible for him to do both. He has to make a choice, a sacrifice. Why would we expect other life choices to be any different? If "having it all" means getting to do everything you want with your life without having to make choices or sacrifices, then no one can have it all, man or woman, because we do have to make hard choices about our lives.

Let me illustrate part of this with my third, narrower point. Slaughter says that we ought not to privilege parents over other workers - which I think is right - and that because women tend to be the primary caregivers, being a parent most often places the burdens of extra work on them rather than equally on both partners. In a two career family, this makes it harder for the woman than for the man. No argument with either of these points so far as I am concerned. But a parable from Slaughter's time at Princeton makes me question how committed she is to the notion that we don't or ought not to privilege parents. She notes that any tenure-track faculty member - male or female - who has a child while at Princeton automatically gets a year added to the tenure clock. I think a lot of us - myself included - reflexively say "that's great!" But why?

My roommate - who really ought to get joint author credit for this post since I'm stealing a lot of his points - made me question why I unflinchingly assumed that new parents ought to get that extra year. Now, there are reasons like "so they can spend more time with their kids" that are obvious, but his critique runs deeper. By enabling new parents to both spend time with their kids and get tenure, we are implicitly saying "having a child is not a choice that should interfere with your career prospects." Again, I think a lot of us say "how great" without actually reflecting on this that much. WHY do we feel that having a child is a choice that shouldn't require that kind of sacrifice? There might be some very good reasons for this; I haven't thought about it enough to say for sure what some of them may or may not be. The point is that we don't feel the need even to articulate such reasons.

Consider the following four scenarios:

1) I put work on the back burner for a year because I just had a child.

2) I put work on the back burner for a year because one of my parents is sick and I move back home to help out around the house.

3) I put work on the back burner for a year because I don't have time to read the classics as avidly as I would like, and I think that I will be a better person and a better academic if I take a year to read and reflect on the classics of world literature (which is, I think, a perfectly colorable argument, by the way).

4) I put work on the back burner for a year because I haven't travelled that much and I think I will be a better person, a more reflective academic, and better cosmopolitan citizen of the world if I visit all seven continents and learn more about cultures in other places.

Each of these represents a life choice a person could very reasonably make to enjoy their life more, enrich their views of the world, nurture familial relationships, be a better person, etc., etc. But the rule that Slaughter finds so much value in at Princeton decides that only one of these choices is one that shouldn't have to interfere with your career (maybe #2 as well, depending on the workplace; but good luck getting your tenure clock in Biology extended to read the complete works of Dante, Cervantes, and Shakespeare, no matter how great a person that might make you). If I end up as a single academic without children, none of the choices I can make to enrich my life at the expense of my work will be one that my university compensates for by ameliorating the negative effects on my career.

Again - I really can't emphasize this enough - we might, on reflection, decide that there are really good reasons to minimize the effect having children has on new parents. If nothing else, people are going to have children, they simply are, no matter how the purported cost/benefit balance is structured. As an old professor of mine put it, "if people thought rationally about having children, no one would ever have any." Given this social/biological fact and its prevalence, we might say that we want to ensure that people can be good parents without abandoning other pursuits. The point, though, is that we don't reflect on it. We tacitly assume that having children is a choice that ought to impact your career as little as possible when we can help it. Why do we assume this? This isn't a rhetorical question meant to imply that we shouldn't; I'm seriously asking what the underlying reasons are. They may require some examination.

Slaughter does such a great job emphasizing the background social norms and default assumptions that make the choices we have to make more problematic for women that it makes it all the more surprising when she doesn't examine nearly as critically the fact that we do privilege married couples and parents at the expense of single people (tax breaks for married couples, for children, leaves of absence or extensions for having kids, etc., etc.; those dollars come from single people, too), even as she says we shouldn't. Especially when the people who make the rules about these things tend to be married people with children, oughtn't we at least look critically at the self-authored rules that privilege their position?

At root, I don't have any real problems with the arguments Slaughter makes, but with the unexamined assumptions that hide behind them. WHY do we feel that we ought to be able to "have it all" without having to make hard choices and sacrifices? WHY do we think that having children is the sort of choice that shouldn't impact your career? Do we have good reasons for these baseline assumptions? And, if not, how does that impact Slaughter's related arguments?

Rules like the one Slaughter favors matter precisely because they privilege one choice (and people who make it) without necessarily encouraging reflection on those privileges and why they are or are not justified. This gets especially dangerous and prickly when we think of something as "natural." Now, I'm pretty sure that procreating is about as natural an activity as we're likely to find, but doing it in marital pairs is subject to (and the result of) all sorts of social norms and pressures (doing it in biological pairs was utterly unavoidable until about thirty years ago). But it's the very description of something as "natural" that encourages us to take it as a given and stop reflecting on how we build our social rules around it.

At root, I'm just encouraging everyone to A) read Slaughter's piece if you haven't already, it's great, but B) consider whether Slaughter's fantasy world without hard life choices is one that can ever exist, and C) critically reflect on the position we place childbearing and rearing in in our political and social spaces, and why we have rules that privilege that choice at the expense of others.

Comments, counterarguments, and the good points I inevitably missed are always welcome, but even more so today, when I have questions that aren't remotely rhetorical.

Thursday, June 21, 2012

Weekly Round-Up for June 22nd

Story of the week: Anne-Marie Slaughter writes for the Atlantic about the patterns that still keep women from "having it all."

But Rebecca Traister thinks we should never use the phrase "have it all" ever again. Ever.

Emily Yoffe tells a personal story about why victims don't report abusers.

In anticipation of the Supreme Court decision on the Affordable Care Act, Jed Shugarman suggests it ought to take six Justices to overturn an act of Congress.

And Richard Thompson Ford suggest an Amendment to break the judicial monopoly on constitutional interpretation.

Dan Markel and Eric Miller want an Amendment to get rid of bail bondsmen.

As part of the same series, Ethan Lieb and Dan Markel argue for an Amendment to strengthen protections against double jeopardy.

LV Anderson explains the consequences of jurors going on dates with parities to the case.

Nathaniel Frank reviews Linda Hirshman's history of gay rights.

Max Perry Mueller discusses murmurs of change on gay issues in the Mormon community.

The New York Times reminds us that those who are already sick have a lot invested in the upcoming Supreme Court decision.

Salon reports on the Supreme Court decision limiting the FCC's power over broadcasters.

David Graham at The Atlantic tells us all we need to know about the Holder debacle.

And Salon gives us an AP story about the House vote on the Holder's contempt.

But Rebecca Traister thinks we should never use the phrase "have it all" ever again. Ever.

Emily Yoffe tells a personal story about why victims don't report abusers.

In anticipation of the Supreme Court decision on the Affordable Care Act, Jed Shugarman suggests it ought to take six Justices to overturn an act of Congress.

And Richard Thompson Ford suggest an Amendment to break the judicial monopoly on constitutional interpretation.

Dan Markel and Eric Miller want an Amendment to get rid of bail bondsmen.

As part of the same series, Ethan Lieb and Dan Markel argue for an Amendment to strengthen protections against double jeopardy.

LV Anderson explains the consequences of jurors going on dates with parities to the case.

Nathaniel Frank reviews Linda Hirshman's history of gay rights.

Max Perry Mueller discusses murmurs of change on gay issues in the Mormon community.

The New York Times reminds us that those who are already sick have a lot invested in the upcoming Supreme Court decision.

Salon reports on the Supreme Court decision limiting the FCC's power over broadcasters.

David Graham at The Atlantic tells us all we need to know about the Holder debacle.

And Salon gives us an AP story about the House vote on the Holder's contempt.

Sunday, June 17, 2012

Pearl Harbor and the Rules of War

"All's fair in love and war," or so the saying goes, but more often it seems that anecdotal evidence and our own instincts suggest otherwise. Right now we debate the merits and demerits of drone attacks, indefinite detentions, torture, etc., etc. All of these have something of the character of "is that something we should do" and/or "is that something we're allowed to do." Which is to say that we wonder aloud whether our wartime (or quasi-wartime) decisions are in-line with both our informal norms and our formal laws.

I've been thinking about this quite a lot lately. I just read a book called "The Admirals," and excellent group biography of the only four men ever to be made five-star Admirals: Halsey, King, Leahy and Nimitz. Two items in particular are worth recounting here. The first is the reticence Nimitz and Leahy in particular had about using the atomic bomb. As defacto Chariman of the Joint Chiefs (before the position existed), Leahy was intimately involved with FDR and the governments plan; Nimitz - Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet - would be responsible for the bombs' delivery. Both men, veterans of WWI and forty-year Navy lifers, felt that leveling cities and extinguishing civilians in the way made possible by the atomic bomb went contrary to warfare as they had learned it at Annapolis and through a lifetime of service.

Though I can't pass judgment on the decision to drop the bomb, I will say that had the war gone differently, there's no doubt that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki would have been considered war crimes, as likely would the firebombing of Dresden

Hiroshima

Nagasaki

Dresden

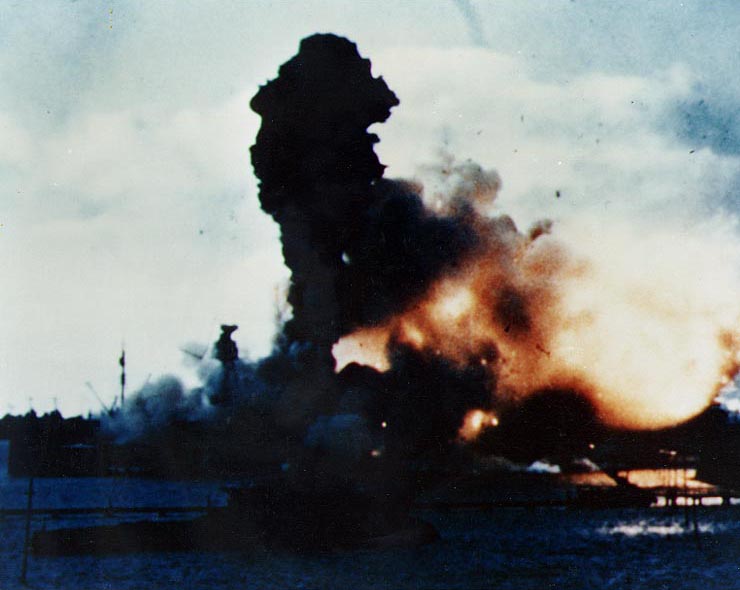

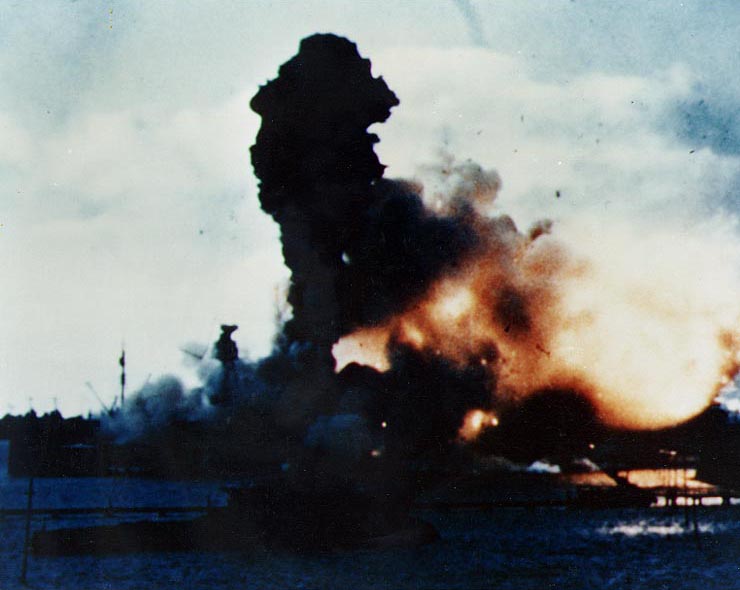

Four years earlier, many had been similarly shocked by the surprise bombing of Pearl Harbor. This, too, was considered by more than a few to be contrary to the conventional rules of declared warfare. Of particular note to visitors these days is the memorial to the Arizona. Just after 8 AM on December 7th, 1941, a bomb tore through the Arizona's deck into the forward magazine and exploded. The resulting blast ripped open the ship.

1,177 men died, many of them are still aboard.

The memorial is moving, beautiful, and altogether well done. The video one watches before taking a boat out to the wreck is even-handed without being cold, emotional without being maudlin. As an experience, I highly recommend it.

Rules of war change all the time, but that isn't to say they aren't real to those experiencing them. In some medieval warfare, armies were maneuvered like pieces on a chess board and the tactically superior commander was declared the winner even if no casualties occurred. We won independence on the back of guerrilla tactics that were, for the time, uncivilized. After the devastation of World War I, we decided as a species that mustard gas, for instance, was no longer an acceptable ordinance to be deployed on the battlefield. And the Geneva Convention continues to establish minimum standards for conduct in battle and off the field.

But it's one thing to say in the calm of peacetime, or in the moments before the heat of battle, that some things are off limits. I have to imagine that when the bombs fall and the bullets fly, things aren't quite so easy.

I want to share one more thing from my trip to Hawaii. While killing time at the Honolulu airport, I struck up conversation with a fellow next to me at the airport bar who turned out to have been a Navy SEAL in Vietnam and Cambodia. He - understandably - doesn't like to talk about the experiences, but after we had talked for an hour about basketball, business, and our discovered Michigan-Ohio State rivalry (and bought each other several drinks a piece), he opened up. He showed me a scar on his leg, and told me - his voice heavy with emotion - that he had been shot by a young Cambodian girl wielding an assault rifle. His voice quivering, he looked right into my eyes and said "I hope you never have to know what it's like to shoot a child."

I hope so too, and it makes me all the more grateful to the men and women who serve and keep me from having to experience things that end up all to common for them. The point, though, is that as the saying goes "no battle plan survives the first encounter with the enemy," and I would venture to say that rules of war rarely survive a full conflict intact. No one ever wants to shoot a child, but the rules change when they're shooting at you.

One more thing from our Navy SEAL friend; it's not law related, but it's worth recounting. As I was leaving, ESPN flashed something about Lebron James' salary. My new friend said "A million here, ten million there." He looked at me, "it'll never make you happy." I asked him what makes him happy, and he smiled. "My wife. My children. Learning. Any day that you learning something new is a good day. That's a good day." He leaned over and touched my arm "from a Buckeye to a Wolverine."

If you're reading this, friend, thank you for your service, and thank you for sharing.

I've been thinking about this quite a lot lately. I just read a book called "The Admirals," and excellent group biography of the only four men ever to be made five-star Admirals: Halsey, King, Leahy and Nimitz. Two items in particular are worth recounting here. The first is the reticence Nimitz and Leahy in particular had about using the atomic bomb. As defacto Chariman of the Joint Chiefs (before the position existed), Leahy was intimately involved with FDR and the governments plan; Nimitz - Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet - would be responsible for the bombs' delivery. Both men, veterans of WWI and forty-year Navy lifers, felt that leveling cities and extinguishing civilians in the way made possible by the atomic bomb went contrary to warfare as they had learned it at Annapolis and through a lifetime of service.

Though I can't pass judgment on the decision to drop the bomb, I will say that had the war gone differently, there's no doubt that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki would have been considered war crimes, as likely would the firebombing of Dresden

Hiroshima

Nagasaki

Dresden

Four years earlier, many had been similarly shocked by the surprise bombing of Pearl Harbor. This, too, was considered by more than a few to be contrary to the conventional rules of declared warfare. Of particular note to visitors these days is the memorial to the Arizona. Just after 8 AM on December 7th, 1941, a bomb tore through the Arizona's deck into the forward magazine and exploded. The resulting blast ripped open the ship.

1,177 men died, many of them are still aboard.

The memorial is moving, beautiful, and altogether well done. The video one watches before taking a boat out to the wreck is even-handed without being cold, emotional without being maudlin. As an experience, I highly recommend it.

Rules of war change all the time, but that isn't to say they aren't real to those experiencing them. In some medieval warfare, armies were maneuvered like pieces on a chess board and the tactically superior commander was declared the winner even if no casualties occurred. We won independence on the back of guerrilla tactics that were, for the time, uncivilized. After the devastation of World War I, we decided as a species that mustard gas, for instance, was no longer an acceptable ordinance to be deployed on the battlefield. And the Geneva Convention continues to establish minimum standards for conduct in battle and off the field.

But it's one thing to say in the calm of peacetime, or in the moments before the heat of battle, that some things are off limits. I have to imagine that when the bombs fall and the bullets fly, things aren't quite so easy.

I want to share one more thing from my trip to Hawaii. While killing time at the Honolulu airport, I struck up conversation with a fellow next to me at the airport bar who turned out to have been a Navy SEAL in Vietnam and Cambodia. He - understandably - doesn't like to talk about the experiences, but after we had talked for an hour about basketball, business, and our discovered Michigan-Ohio State rivalry (and bought each other several drinks a piece), he opened up. He showed me a scar on his leg, and told me - his voice heavy with emotion - that he had been shot by a young Cambodian girl wielding an assault rifle. His voice quivering, he looked right into my eyes and said "I hope you never have to know what it's like to shoot a child."

I hope so too, and it makes me all the more grateful to the men and women who serve and keep me from having to experience things that end up all to common for them. The point, though, is that as the saying goes "no battle plan survives the first encounter with the enemy," and I would venture to say that rules of war rarely survive a full conflict intact. No one ever wants to shoot a child, but the rules change when they're shooting at you.

One more thing from our Navy SEAL friend; it's not law related, but it's worth recounting. As I was leaving, ESPN flashed something about Lebron James' salary. My new friend said "A million here, ten million there." He looked at me, "it'll never make you happy." I asked him what makes him happy, and he smiled. "My wife. My children. Learning. Any day that you learning something new is a good day. That's a good day." He leaned over and touched my arm "from a Buckeye to a Wolverine."

If you're reading this, friend, thank you for your service, and thank you for sharing.

Friday, June 15, 2012

Weekly Round-Up for June 15th

As always, links to some of the week's best stories:

It's not necessarily law, but it's SO cool: Voyager I is about to leave the solar system.

Emily Bazelon thinks Jerry Sandusky should plead guilty right now (yesterday or earlier if possible).

Heather Gerken thinks we should amend the Constitution to guarantee the right to vote. Which it does not.

Dahlia Lithwick explains how Justice Kennedy is just like America.

Ms. Lithwick (may I call you Dahlia) also wonders about the Supreme Court's relationship to the press.

At Salon, John Sodoro writes about the increased scrutiny on neighborhood watch groups.

Alex Seitz-Wald tells us about Alabama voters' chance to finally strike Jim Crow language from their constitution.

Over at The Atlantic, Brian Wansink and David Just argue that NYC's soft-drink ban will backfire.

And Ta-Nehisi Coates explores the limits of standing your ground.

It's not necessarily law, but it's SO cool: Voyager I is about to leave the solar system.

Emily Bazelon thinks Jerry Sandusky should plead guilty right now (yesterday or earlier if possible).

Heather Gerken thinks we should amend the Constitution to guarantee the right to vote. Which it does not.

Dahlia Lithwick explains how Justice Kennedy is just like America.

Ms. Lithwick (may I call you Dahlia) also wonders about the Supreme Court's relationship to the press.

At Salon, John Sodoro writes about the increased scrutiny on neighborhood watch groups.

Alex Seitz-Wald tells us about Alabama voters' chance to finally strike Jim Crow language from their constitution.

Over at The Atlantic, Brian Wansink and David Just argue that NYC's soft-drink ban will backfire.

And Ta-Nehisi Coates explores the limits of standing your ground.

Monday, June 11, 2012

Naked Pictures and Sleeping in Public, or: A Plane Ride

Next week, a post on the Arizona memorial and my moving encounter with a Navy SEAL at the Honolulu airport. In the meantime, an off day meander through privacy.

Under normal circumstances, I would find the idea of people watching me sleep distasteful, at best. We rarely - if ever - sleep in front of people to whom we aren't related, or with whom we aren't involved. When was the last time strangers saw you sleep? Ten bucks says it was on either an airplane or a bus.

I slept on the plane from Honolulu to Chicago, as did a great many other people on that place. I got me thinking about the personal norms and boundaries we relax when we fly. It isn't just sleeping in front of strangers, it's all of the little indignities that attend sleep and its aftermath: the stretches, the yawns, the breath and breathing, the open mouths, the snoring, the occasional bit of drool, etc., etc. These are things that are normally only seen by our intimates. As Paul Reiser has noted in his comedy, and William Ian Miller argues extensively (and compellingly) in The Anatomy of Disgust, these little - occasionally gross - indignities represent a strong social boundary. We relax our personal boundaries and expand what are normally private matters for those we love.

Think about the various boundaries we blur or standards we lower when we travel. It isn't just that we sleep in front of others, it's that we eat food we normally would not, or at least not for what we're required to pay on a flight ($9.00 for a crappy set of spreads and crackers? Really, United?). We watch movies we wouldn't watch unless captive (I suffered through "One for the Money" - which I recommend avoiding at all possible costs - but even in such captivity I refused the offering of "The Vow"). We are forced to tolerate the screaming infants we wouldn't in almost any other setting. The private rules by which we live our lives are suspended when we travel.

Nowhere is this more obvious that in the indignities we suffer in security. Where else would we possibly agree to stand in line for the privilege of removing our shoes, having our personal items x-rayed, and having naked pictures taken of us?

And all of this as a matter of course. We rarely even think of what an incredible intrusion this would be in almost any other circumstance. Most of the time we just do it.

My point, I suppose, is that while I've mostly written about how society and social norms interact with our official rules and laws, those aren't the only times that society dictates reinterpretations of a set of rules or norms. In the case I'm exploring here, it's the personal rules that we normally thinking as not only traveling with us but as being part of our identity - our standards are most assuredly part of who we are.

But even these rules that we consider part of our very persona - and that we allegedly take with us wherever we go - are subject to the vagaries and impacts of the social settings between which we constantly move. Just as we use words with our friends down at the bar that we wouldn't use with our significant other's parents, things we absolutely wouldn't allow at work, at school, at a restaurant, or even in our homes (most of the time) we take as a matter of course in an airport or on a plane.

I don't think this suggests that our personal standards are meaningless or arbitrary. More probably they're just far more complex than we often realize. When we say, "I would never watch 'One for the Money,'" what we actually mean is "I would never watch 'One for the Money' unless I had nothing else on my laptop to watch and had a neck ache that prevents me from reading and it's on right in front of me." But it's not a particularly efficient way to describe our standards, and we often don't discover the exceptions to our standards until we confront them (the exceptions) (also the standards).

I don't think this suggests that our personal standards are meaningless or arbitrary. More probably they're just far more complex than we often realize. When we say, "I would never watch 'One for the Money,'" what we actually mean is "I would never watch 'One for the Money' unless I had nothing else on my laptop to watch and had a neck ache that prevents me from reading and it's on right in front of me." But it's not a particularly efficient way to describe our standards, and we often don't discover the exceptions to our standards until we confront them (the exceptions) (also the standards).

So the next time some one sneezes next to you on a plane, or reveals a secret that seems a little too personal, or in someway offends your sense of decorum, consider the setting. I'm not saying forgive the others immediately - what would the fun in that be - but rather to encourage you to think about the inherent flexibility built into your standards that often flies under the radar.

Under normal circumstances, I would find the idea of people watching me sleep distasteful, at best. We rarely - if ever - sleep in front of people to whom we aren't related, or with whom we aren't involved. When was the last time strangers saw you sleep? Ten bucks says it was on either an airplane or a bus.

I slept on the plane from Honolulu to Chicago, as did a great many other people on that place. I got me thinking about the personal norms and boundaries we relax when we fly. It isn't just sleeping in front of strangers, it's all of the little indignities that attend sleep and its aftermath: the stretches, the yawns, the breath and breathing, the open mouths, the snoring, the occasional bit of drool, etc., etc. These are things that are normally only seen by our intimates. As Paul Reiser has noted in his comedy, and William Ian Miller argues extensively (and compellingly) in The Anatomy of Disgust, these little - occasionally gross - indignities represent a strong social boundary. We relax our personal boundaries and expand what are normally private matters for those we love.

Think about the various boundaries we blur or standards we lower when we travel. It isn't just that we sleep in front of others, it's that we eat food we normally would not, or at least not for what we're required to pay on a flight ($9.00 for a crappy set of spreads and crackers? Really, United?). We watch movies we wouldn't watch unless captive (I suffered through "One for the Money" - which I recommend avoiding at all possible costs - but even in such captivity I refused the offering of "The Vow"). We are forced to tolerate the screaming infants we wouldn't in almost any other setting. The private rules by which we live our lives are suspended when we travel.

Nowhere is this more obvious that in the indignities we suffer in security. Where else would we possibly agree to stand in line for the privilege of removing our shoes, having our personal items x-rayed, and having naked pictures taken of us?

And all of this as a matter of course. We rarely even think of what an incredible intrusion this would be in almost any other circumstance. Most of the time we just do it.

My point, I suppose, is that while I've mostly written about how society and social norms interact with our official rules and laws, those aren't the only times that society dictates reinterpretations of a set of rules or norms. In the case I'm exploring here, it's the personal rules that we normally thinking as not only traveling with us but as being part of our identity - our standards are most assuredly part of who we are.

But even these rules that we consider part of our very persona - and that we allegedly take with us wherever we go - are subject to the vagaries and impacts of the social settings between which we constantly move. Just as we use words with our friends down at the bar that we wouldn't use with our significant other's parents, things we absolutely wouldn't allow at work, at school, at a restaurant, or even in our homes (most of the time) we take as a matter of course in an airport or on a plane.

So the next time some one sneezes next to you on a plane, or reveals a secret that seems a little too personal, or in someway offends your sense of decorum, consider the setting. I'm not saying forgive the others immediately - what would the fun in that be - but rather to encourage you to think about the inherent flexibility built into your standards that often flies under the radar.

Monday, June 4, 2012

The Law of the Splintered Paddle

Aloha from Oahu! This week's post is coming to you from the middle of the Pacific; I'm writing this while looking at the Mokulua Islands of off Kailua.

As befits such a post, I want to talk a little bit about the Hawaiian legal tradition; in particular "The Law of the Splintered Paddle." I'll be a bit more reporter than analyst today, but it's a fascinating story worth the telling. And now, "The Law of the Splintered Paddle."

While fighting in Puna in the late 1700's, King Kamehameha got his foot stuck in a reef and one of the fisherman he was pursuing struck him over the head with an oar, splintering it.

Later, the same fisherman was brought before the King, but rather than have him killed, Kamehameha purportedly said "Let every man, woman, and child lie by the roadside in safety." The fisherman had only been defending himself, as any man would be expected to do, and to punish him would therefore be unjust. This precept, however, did not originate with Kamehameha. Rather, it is an ancient Hawaiian tradition that boils down to this: political legitimacy depends on fair and humane treatment of one's people. Over the centuries, story after story has accumulated of Hawaiian rulers who were deposed - and sometimes executed - because of their unfair or inhumane treatment of their subjects. The Law of the Splintered Paddle was in some ways the culmination of centuries of political and legal evolution.

What's interesting - well, what's also interesting - is that this particular legal precept has worked its way through centuries of Hawaiian rule, was first codified in 1797 under Kamehamhea, and survived the transition from independent Pacific Kingdom to annexed territory to state and currently exists in the Hawaii State Constitution (Article 9, Section 10, for interested parties).

Though ostensibly a legal rule - it's now a constitutional provision, after all - what's really happened is that an informal legal/political norm (treat your subjects well or its curtains) influenced legal-political decision making over centuries of political rule, was finally codified as "Let every man, woman, and child lie by the roadside in safety," (which seems to mean "don't do bad stuff and nothing bad will happen to you") and has now found a home in a modern constitution as a cross between a legal precept ("we will protect our citizens and their rights demand it") and a rule of statutory interpretation ("political and legal legitimacy depends on the respect of the health, safety, and rights of the citizens").

I don't know much (read: anything) about how the rule currently alters the legal landscape in the state of Hawaii. What's of note, I think, is that a long held socio-political tradition (not even a rule, narrowly understood, but an informal tradition) survived the centuries and multiple paradigm shifts to the political order and remains in effect today. I think it's an instructive example of how social norms evolve, endure, and shape not only our legal landscape, but our legal evolution.

Mahalo for reading, and once again: Aloha from Oahu! Be sure to come back over the next two weeks for a report from the Law and Society Annual Meeting and a reflection from the memorials at Pearl Harbor.

As befits such a post, I want to talk a little bit about the Hawaiian legal tradition; in particular "The Law of the Splintered Paddle." I'll be a bit more reporter than analyst today, but it's a fascinating story worth the telling. And now, "The Law of the Splintered Paddle."

While fighting in Puna in the late 1700's, King Kamehameha got his foot stuck in a reef and one of the fisherman he was pursuing struck him over the head with an oar, splintering it.

Later, the same fisherman was brought before the King, but rather than have him killed, Kamehameha purportedly said "Let every man, woman, and child lie by the roadside in safety." The fisherman had only been defending himself, as any man would be expected to do, and to punish him would therefore be unjust. This precept, however, did not originate with Kamehameha. Rather, it is an ancient Hawaiian tradition that boils down to this: political legitimacy depends on fair and humane treatment of one's people. Over the centuries, story after story has accumulated of Hawaiian rulers who were deposed - and sometimes executed - because of their unfair or inhumane treatment of their subjects. The Law of the Splintered Paddle was in some ways the culmination of centuries of political and legal evolution.

What's interesting - well, what's also interesting - is that this particular legal precept has worked its way through centuries of Hawaiian rule, was first codified in 1797 under Kamehamhea, and survived the transition from independent Pacific Kingdom to annexed territory to state and currently exists in the Hawaii State Constitution (Article 9, Section 10, for interested parties).

Though ostensibly a legal rule - it's now a constitutional provision, after all - what's really happened is that an informal legal/political norm (treat your subjects well or its curtains) influenced legal-political decision making over centuries of political rule, was finally codified as "Let every man, woman, and child lie by the roadside in safety," (which seems to mean "don't do bad stuff and nothing bad will happen to you") and has now found a home in a modern constitution as a cross between a legal precept ("we will protect our citizens and their rights demand it") and a rule of statutory interpretation ("political and legal legitimacy depends on the respect of the health, safety, and rights of the citizens").

I don't know much (read: anything) about how the rule currently alters the legal landscape in the state of Hawaii. What's of note, I think, is that a long held socio-political tradition (not even a rule, narrowly understood, but an informal tradition) survived the centuries and multiple paradigm shifts to the political order and remains in effect today. I think it's an instructive example of how social norms evolve, endure, and shape not only our legal landscape, but our legal evolution.

Mahalo for reading, and once again: Aloha from Oahu! Be sure to come back over the next two weeks for a report from the Law and Society Annual Meeting and a reflection from the memorials at Pearl Harbor.

Friday, June 1, 2012

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)