Noticeably absent from Code of the Street is a sufficient discussion of how mass incarceration affects the kinds of communities that Elijah Anderson was examining. In particular, chapters four and five are titled “The Mating Game” and “The Decent Daddy;” with regard to these subjects, the disproportionate numbers of black men who are incarcerated or have interacted with the criminal justice system is absolutely relevant to the role of black men in relationships and in families.

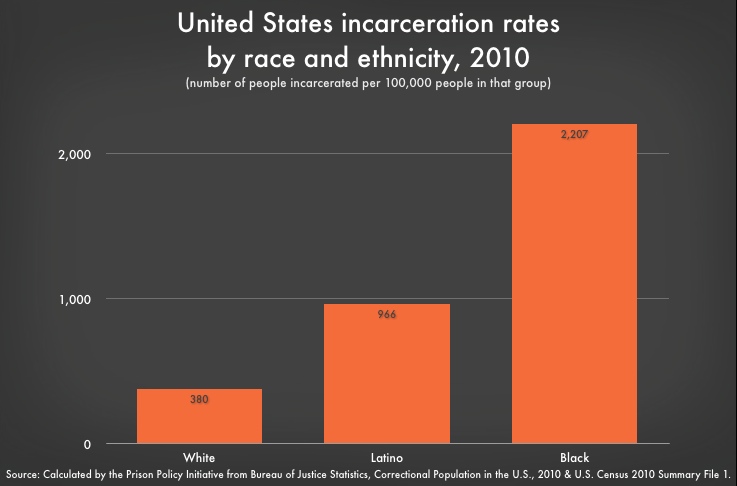

When Elijah Anderson analyzes the appeal of the street life, he discusses the attractiveness of the drug trade to these populations. He notes that, although it is illegal, “it is the most lucrative and most accessible element of the underground economy” (111). Not only is it a lucrative opportunity, but for many black men it may be their only economic opportunity. Anderson notes that many young black men have trouble finding an above-ground job due to racial discrimination, and may fail to even begin the job search under this assumption and observation that they will be passed over regardless (111). In such circumstances, it may seem rational to engage in drug dealing; however, that does not make the activity any less illegal. Even though Anderson claims that the deep-rooted connection between drugs and inner-city life is “largely tolerated by civic authorities and the police,” there is contradictory empirical evidence that black men in particular face steep consequences for such activity (111). The War on Drugs exacerbated racial disparities in our prison systems to the point that two-thirds of all drug offenders in prison are people of color.

There is vast empirical evidence which clearly shows the direct effect of mass incarceration on black men; more subtly and indirectly, this trend also has an effect on black women. The Economist published an article to this effect in 2010, looking at “how the mass incarceration of black men hurts black women.” It noted that one in nine black men aged 20-29 is in jail or prison; for black women in this age range, the numbers were only one in 150. Most people marry someone of the same race, but people behind bars can be assumed to be excluded from the dating pool, so these skewed numbers present a real challenge in the mating game. As evidence of this fact, the article found that “as incarceration rates exploded between 1970 and 2007, the proportion of US-born black women aged 30-44 who were married plunged from 62% to 33%.” Elijah Anderson’s analysis of the mating game in Code of the Street is compatible with the phenomenon described in this article. Anderson discussed the social factors for low marriage rates, explaining how marrying for love is a privileged mind-set that “presupposes a job, the work ethic, and, perhaps most of all, a persistent sense of hope for an economic future” (178). The lack of these positive factors is directly related to the expansion of the drug culture and the uncertainty of drug dealing as a form of income, which is far less conducive to sustaining a family compared to traditional employment. We can see that not only is incarceration affecting marriage rates due to the physical obstacle it presents, but even the factors that could lead to future incarceration (like engaging with the drug trade) coincide with factors decreasing the likelihood of marriage.

Related to this debate on the lack of eligible black men for marriage is the public discourse regarding absent black fathers. President Obama spoke about this subject on the 2008 campaign trail, arguing that “Too many fathers are M.I.A. Too many fathers are AWOL. They have abandoned their responsibilities, acting like boys instead of men. And the foundations of our families are weaker because of it. We know this is true everywhere, but nowhere is this more true than in the African American community.” Elijah Anderson similarly enforced this stereotype of the missing black father in the context of his discussion on “decent daddies.” He noted that if young men feel they are unable to “make the woman love him without his resorting to abuse” they may drop out of this game of playing house; they shirk responsibility and are, “at best, part-time fathers and partners” (186). His case studies of two decent daddies present them as exceptions to the rule. Contrary evidence is offered by Michelle Alexander, author of the New Jim Crow. She notes in her book that all the people who proliferate the stereotype of the missing black father fail to offer where we will likely find them – in prison. One million of the ‘missing’ black men in our society can be found in jails or prisons, but the public acknowledgement of this fact is too rare. She offered research showing that, contrary to this stereotype of the absent black father, “black fathers not living at home are more likely to keep in contact with their children than fathers of any other ethnic or racial group” (179).

Mass incarceration is a problem that intersects many issues of inner-city life that Anderson examined, such as involvement with the drug trade, racial prejudice, and street vs decent families. Directly, it is a problem affecting black men, but the indirect effects are felt by their partners and children. By understanding the scope of mass incarceration’s interference with the black community, we can gain a more complete understanding of the problems described by Anderson in Code of the Street.