Noticeably absent from Code of the Street is a sufficient discussion of how mass incarceration affects the kinds of communities that Elijah Anderson was examining. In particular, chapters four and five are titled “The Mating Game” and “The Decent Daddy;” with regard to these subjects, the disproportionate numbers of black men who are incarcerated or have interacted with the criminal justice system is absolutely relevant to the role of black men in relationships and in families.

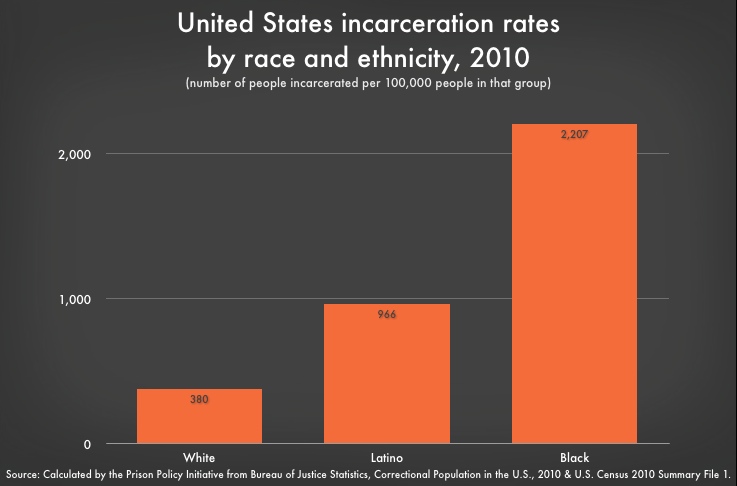

When Elijah Anderson analyzes the appeal of the street life, he discusses the attractiveness of the drug trade to these populations. He notes that, although it is illegal, “it is the most lucrative and most accessible element of the underground economy” (111). Not only is it a lucrative opportunity, but for many black men it may be their only economic opportunity. Anderson notes that many young black men have trouble finding an above-ground job due to racial discrimination, and may fail to even begin the job search under this assumption and observation that they will be passed over regardless (111). In such circumstances, it may seem rational to engage in drug dealing; however, that does not make the activity any less illegal. Even though Anderson claims that the deep-rooted connection between drugs and inner-city life is “largely tolerated by civic authorities and the police,” there is contradictory empirical evidence that black men in particular face steep consequences for such activity (111). The War on Drugs exacerbated racial disparities in our prison systems to the point that two-thirds of all drug offenders in prison are people of color.

There is vast empirical evidence which clearly shows the direct effect of mass incarceration on black men; more subtly and indirectly, this trend also has an effect on black women. The Economist published an article to this effect in 2010, looking at “how the mass incarceration of black men hurts black women.” It noted that one in nine black men aged 20-29 is in jail or prison; for black women in this age range, the numbers were only one in 150. Most people marry someone of the same race, but people behind bars can be assumed to be excluded from the dating pool, so these skewed numbers present a real challenge in the mating game. As evidence of this fact, the article found that “as incarceration rates exploded between 1970 and 2007, the proportion of US-born black women aged 30-44 who were married plunged from 62% to 33%.” Elijah Anderson’s analysis of the mating game in Code of the Street is compatible with the phenomenon described in this article. Anderson discussed the social factors for low marriage rates, explaining how marrying for love is a privileged mind-set that “presupposes a job, the work ethic, and, perhaps most of all, a persistent sense of hope for an economic future” (178). The lack of these positive factors is directly related to the expansion of the drug culture and the uncertainty of drug dealing as a form of income, which is far less conducive to sustaining a family compared to traditional employment. We can see that not only is incarceration affecting marriage rates due to the physical obstacle it presents, but even the factors that could lead to future incarceration (like engaging with the drug trade) coincide with factors decreasing the likelihood of marriage.

Related to this debate on the lack of eligible black men for marriage is the public discourse regarding absent black fathers. President Obama spoke about this subject on the 2008 campaign trail, arguing that “Too many fathers are M.I.A. Too many fathers are AWOL. They have abandoned their responsibilities, acting like boys instead of men. And the foundations of our families are weaker because of it. We know this is true everywhere, but nowhere is this more true than in the African American community.” Elijah Anderson similarly enforced this stereotype of the missing black father in the context of his discussion on “decent daddies.” He noted that if young men feel they are unable to “make the woman love him without his resorting to abuse” they may drop out of this game of playing house; they shirk responsibility and are, “at best, part-time fathers and partners” (186). His case studies of two decent daddies present them as exceptions to the rule. Contrary evidence is offered by Michelle Alexander, author of the New Jim Crow. She notes in her book that all the people who proliferate the stereotype of the missing black father fail to offer where we will likely find them – in prison. One million of the ‘missing’ black men in our society can be found in jails or prisons, but the public acknowledgement of this fact is too rare. She offered research showing that, contrary to this stereotype of the absent black father, “black fathers not living at home are more likely to keep in contact with their children than fathers of any other ethnic or racial group” (179).

Mass incarceration is a problem that intersects many issues of inner-city life that Anderson examined, such as involvement with the drug trade, racial prejudice, and street vs decent families. Directly, it is a problem affecting black men, but the indirect effects are felt by their partners and children. By understanding the scope of mass incarceration’s interference with the black community, we can gain a more complete understanding of the problems described by Anderson in Code of the Street.

Hi Laura, I think your analysis is not only very well thought out and articulated, but also so relevant given current events. Incarceration undoubtedly influences countless domains of lifestyle for groups who are unequally affected by the current system in place. I read an article that after a community police force used the guest sign-in sheet at a hospital to track down and arrest a black drug user, other black men and women in that community were less likely to seek health care out of fear. Incarceration patterns, and the resulting distrust, can not only, as you mentioned, influence the role individuals of color feel they can occupy in their communities, but also the type of resources they feel that they have legitimate access to.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the comments, Jihad! That example you provided is at once shocking and unsurprising. I just completed a term paper for another class on the subject of “crimmigration,” examining our nation’s increasingly tough immigration policies (with the notable example of Arizona SB 1070). In my research, I discovered something that strongly reminds me of your example. I learned that there are policies which exist to protect the rights of unaccompanied and undocumented juveniles who are taken in custody, such as the preference that they be released to the care of parents or relatives as opposed to detained. However, the Department of Homeland Security has been found to manipulate this preference for family reunification. When children are released from the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, ORR notifies DHS of the child’s release. With this information, DHS then apprehends and redetains children, this time with their parents. It is so appalling how law enforcement repeatedly takes advantage of institutions put in place to help people.

DeleteI think you did a great job discussing an issue further that Elijah Anderson somewhat sweeps over. Mass incarceration clearly has a massive impact on the relatives of the prisoner, especially their spouse/partner and children. I believe you could have taken your analysis one step further and looked specifically at incarceration rates within families. Are those children with fathers in the prison system more likely to end up getting incarcerated? Although the ratio of black women in the criminal justice system is much smaller than black men, are those women’s spouses/partners jailed as well? These statistics, if available, could have provided more insight into mass incarceration’s direct effects on families.

ReplyDeleteIt could have also been interesting to look into the effects mass incarceration is having on another group – “inner-city grandmothers”. As Ellickson states, “When more options become available…and the miseries of poverty, drugs, and violence recede, the heroic grandmother may once again retire to the wings, because her role is perceived to be less necessary, socially and economically” (210). However, when incarceration is directly affecting a family, it would seem likely that grandmothers would take on a greater role of caring and nurturing for those outside of the prison walls. Looking into this group could have painted a more comprehensive picture of the overall effects mass incarceration has on family structure and the roles within a household.

Hi Michelle, that’s a great point about looking at rates of incarceration among the children of the incarcerated. I was inspired to do some quick research on the subject, but I’m coming up with controversial results. I think it is because a lot of the information about the children of the incarcerated comes from advocate organizations supporting them; it is already such a complex and vulnerable position to be in when a parent is in prison or jail, and I am not sure anyone would want to argue that one might also then be predisposed to criminality because of these circumstances (even if it provides further evidence of the destructiveness of incarceration).

DeleteHowever, I think that the effects of having an incarcerated parent on one’s behavior and school performance in combination with the “school-to-prison pipeline” could definitely lead to increased risk of incarceration. Being separated from one’s parent can naturally lead to emotions of anxiety, depression, and anger; these can manifest in children acting out, performing poorly in school, and even neglecting to show up. This can have terrible consequences because of the national trend towards “zero-tolerance” policies and the increased police presence in our schools. Increasingly, students are suspended, expelled, or sent to the police station for minor infractions that do not warrant such severe punishment, while also depriving them of the opportunity to receive an education. This is another effect of mass incarceration in our country: our schools are beginning to look more like prisons, instead of us trying to make our prisons look more like schools.

In Code of the Street, Anderson does a great job of explaining the norms on the street, their development and evolution, their origins and reasons for existence, and some of their direct impacts on the community in question. However, it's important for us to have a separate discussion, about the long-term ramifications of The Code (which you've brought up with this paper). It is becoming clearer and clearer that, not only are we failing to solve, effectively, the issues that lead to incarceration, but that incarceration is a terrible and potentially harmful solution, or way of contending with, legal violations. Anderson shows this to be true when he talks about the fact that people who smoke crack out of a pipe are more likely to be convicted and sentenced to longer terms than those who are found using powdered cocaine. Even though these crimes are virtually identical, the current prison system engenders resentment in the minority community by harshly punishing them for crimes that others' have received no or minimal penalties for committing. Ultimately, this leads to disillusionment with the legal system (which is, obviously, a big topic in the news right now), and can drive people to become so distrustful and skeptical of the system that is meant to protect them (but does not), that they understandably become renegades. If there exists undeniable prejudice in a legal system, why should those who are on the receiving end of the prejudice feel like they have to adhere to laws that do not really protect them anyway? The mass-incarceration is slated to cause extreme sociological problems, not only by reducing the number of mates available to start families, but also by reducing influence and opportunities (you can't go to school, be employed, or vote if you're imprisoned). Anderson explicitly talks about the grave ramifications, including increased instances of crime, violence, etc., of children growing up without fathers, yet, ironically, this society continues to take fathers away from their children for the sake of creating a better society. Why is this happening? I think this question can be answered with another question: who does this benefit? The answer is the dominant class, which has a vested interest in maintaining the status quo in order to maintain its privileges, as unfair as this may be. Let's not blame individuals, though. The rational choice model would support the idea that individuals have their best interests in mind, which would explain why they are trying to maintain the status quo. It's possible that subjugating other people is merely a byproduct of this. What we must realize, though, is that the system needs changing. Incentives need to be changed so that people are more willing to apply the research we've done on this topic and make useful and profound changes that do not include incarcerating people, which has been shown to result in future incarcerations.

ReplyDeleteYou did a fantastic job picking up on a detail I had not considered when doing the readings. An interesting factor to expand on is the way the facts of incarceration impact the behavior of both men and women outside of prison walls.

ReplyDeleteMen might be inclined to act a certain way in the mating game, because a man is a more rare commodity in this community. Men can therefore get away with moving from one woman to the next as Anderson told us is glorified among men in his peer group.

Woman act differently as they try to be one of the few who end up with a partner. This can be seen in the way they attempt to get pregnant, and secure men.

I think your paper highlighted some important aspects of mass incarceration that barely gets talked about . In one part you note how many ‘missing’ black men are actually in prison but the general public does not really pay attention to this fact. It showed a sharp contrast to the fact that the United States (currently) imprisons more black men than apartheid South Africa did yet SA had institutionalized racism while the USA portrays it as being post-racial. To me, it seemed like black men in prison is seen as common and undefended but also a fact that is beginning to gain more attention with the events that have occurred recently. I also found it interesting when you challenged the stereotype that African-American men are absent fathers but it led me to question why Anderson’s discussion did not offer any, if at all, argument about fathers who actually maintain contact with their children besides his two ‘decent daddies’ example.

ReplyDeleteI think you were really effective in analyzing the effects of incarceration within the family dynamics of Anderson’s Code of the Street. It is possible that such mass incarceration contributes to the instability of relationships, before children even come into the picture. Thus, I wonder if the women in Code of the Street in turn intentionally become pregnant to secure their relationships when the fathers of their children return from prison. Additionally, it is interesting to note that many fathers in prison do not see “fatherhood” as a defining characteristic of their identity. Perhaps this is because many of these men have fathered multiple children, or have not had the unique bonding experience with their children that mothers typically experience.

ReplyDeleteJenifer McShane’s documentary Mothers of Bedford follows a group of mothers in Bedford Hill’s prison, which has one of the most comprehensive child-care programs for mothers in prison in the country. According to the documentary, 80% of women in United States women today are actually mothers of school age children. The film follows five women as they struggle to become better mothers while inside a maximum-security prison, and it is fascinating to see that even though they have been separated from their children, they still consider “motherhood” as the foremost defining characteristic. Studies have suggested that a mother-child relationship is arguably the single most important relationship in a developing child’s life, but how are children faring after their fathers to the prison system? If more prisons like Bedford had programs to help parents continue to develop relationships with their children, how would this benefit the family? Could the same type of program work in a men’s prison? These are all questions I think our prison system needs to revisit in order to benefit the health and emotional well-being of both parents in prison, and young children outside of prison.

You made a very important point at directing the view away from the observed street towards what apparently remained invisible even to Anderson. The prison might be even more than just a blind spot for exclusion from society. Social life does not end with incarceration and especially when many members of a society enter a prison at some point linkages are created. Strict prison systems and frequent incarceration sentences for small crimes have been revealed to actually support the formation and growth of gang networks up to the creation of a gang's honor code dominating social life in a prison. I think it is reasonable to consider tha the honor code of a prison shows many similarities to the honor code of the street, with the exclusion of mating and family related issues. Therefore, a mutual influence and self-reinforcing cycle could be present that has not been taken into account for the analysis of the genesis of the street code. Once the prison becomes an important living space for a considerable number of members of a society, its influences on social norms cannot be ignored. Especially the idiosyncratic living conditions of a prison may impact the otherwise perfectly aligning comparison between "street" and "decent" and complicate the search for the origin of the street society.

ReplyDeleteI think you did an awesome job articulating the book material while adding relevant outside sources to further it. As we read, incarceration has become a socioeconomic social norm for the male African American racial group. This leads to staggering numbers of young males ending up in prison from civil disputes through mandatory sentencing laws. In turn this affects woman in the same socioeconomic group. I took a Political Philosophy course last semester, and we spoke extensively about how we marry within our own socioeconomic group. In this case, since more and more men are being sent to jail, more and more woman are having children out of wedlock from multiple men raised without a constant father figure in their lives. The system is failing to help these persons as it has started a domino effect through trying to crack down and reinforce strict policing

ReplyDeleteLaura, that was a very well articulated piece of writing and you did an excellent job picking up on a topic that wasn’t well covered by Anderson. In relation to your topic, you spoke on how the drug game is typically a black male’s only economic opportunity. Another way you could elaborate on this would be why it’s their only opportunity. Anderson discusses how in order to walk in peace, sometimes you have to dress the part, he explains, “Malik and Tyree often dress to look mean or cool, as though they ‘are not for foolishness’-not to be messed with.” This identity crisis also hinders their ability to get a job, because it dissatisfies employers, however keeps them safe on the street and forces them to the drug game as a last resort. Again, it seems as though the root of this problem lies in the failure of the government to act and respond, as there is a lack of faith in the laws that perpetuates this cycle.

ReplyDeleteLaura, that was a very well articulated piece of writing and you did an excellent job picking up on a topic that wasn’t well covered by Anderson. In relation to your topic, you spoke on how the drug game is typically a black male’s only economic opportunity. Another way you could elaborate on this would be why it’s their only opportunity. Anderson discusses how in order to walk in peace, sometimes you have to dress the part, he explains, “Malik and Tyree often dress to look mean or cool, as though they ‘are not for foolishness’-not to be messed with.” This identity crisis also hinders their ability to get a job, because it dissatisfies employers, however keeps them safe on the street and forces them to the drug game as a last resort. Again, it seems as though the root of this problem lies in the failure of the government to act and respond, as there is a lack of faith in the laws that perpetuates this cycle.

ReplyDeleteLove the blog post! I think your analysis on "the missing black father" really hits at the heart of the major inequalities in our judicial system. I understand trying to advocate for personal responsibility, but much of those arguments ignore centuries of systemic oppression and a current legal code that discriminates by race in all but name. However, it would be interesting to see how attitudes like the ones displayed by Anderson (or even President Obama) influence black culture and its interactions with "mainstream" (aka White) society. Few black men abandon their families without cause; either work or prison often force them to work outside the law to gain any hope of economic advancement and identity. When powerful public figures actively admonish black men for not being around for their children or wives, especially when they don't seem to address the socio-economic and political disparities that led to the rise in 'broken homes,' it reinforces the view that blacks have to "work against" an unjust system. Instead of getting help from friendly officials, they get blamed for the current state of affairs. In order to build up a new trust in the system, public officials must send clear signals that the laws will apply equally to everyone.

ReplyDeleteI think that this post is extremely relevant in light of recent events. There is this myth that the everyone is equal under the law but as we have seen recently on the news, this is largely false. As displayed in the book, A Time to Kill and movie, Twelve Angry Men, the eyes of the law are human eyes and as such, it is incredibly difficult to keep social identity out of the picture. With this in mind it is easy to see how potential for prejudice, even if subconscious, could affect the verdict of a jury. I think the clearest example of this is the Eric Garner case that recently took place where by the indisputable evidence, CAUGHT ON FILM, still resulted in no indictment for the white cop that killed him. There are few other explanations for the jury's verdict than identity influences. That being said, it seems one could assume that when it works as such for white cops, this phenomena could also work in a similar manner, but with opposite outcome, for accused black men, possibly contributing to the mass incarceration rates.

ReplyDeleteGreat analysis on the significance of mass incarceration at it related to physical communities of color, specifically the black community. While understanding the ways in which mass incarceration plays an impact on the black family, I think that acknowledging the greater impacts of the black community as a whole would be beneficial in looking at the broader scope of black incarceration and family structure in the United States. Some of these impacts are indirectly, and some argue directly, related to the legacy of racism and racialized oppression in US history. As articulated in the recent articles and videos on Ferguson and the criminal justice system, the legacy of slavery and other racial projects (a term cultivated by Michael Omi and Howard Winant) throughout US history has disproportionately disadvantaged the black community as whole. Thus, many of the existing disparities could be linked to that legacy, i.e. mass incarceration and Elijah Anderson's findings. Overall, I think that this post and the analyses that have been brought up in the comments provide great insight and room for discussion about the recent racial tensions in the United States.

ReplyDelete