As always, stories that caught my eye this week:

When it comes to Mexico and immigration, turnabout is fair play.

Dahlia Lithwick explains why Antonin Scalia is the justice most likely to get profiled as a paid Fox News Correspondent.

Andrew Cohen weighs in on the Arizona case as well.

David Wiegel reviews Robert Draper's new book and wonders if this is the worst congress ever.

Slate yearns for a time when we looked up to accomplished people instead of Kim Kardashian.

Slate links to a Longform piece on stories about coming out.

At Salon, Steve Kornacki explains how Obama's hopes for a second term depend more on George W. Bush than you think.

Rupert Murdoch turns the tables on the British Government; the empire strikes back indeed.

A professor who used to teach about corporate fraud has been sentenced for corporate fraud. Apparently it was a clinic.

Bob Dylan is going to be awarded the Medal of Freedom. Think POTUS will sing?

P.L. Thomas thinks Presidents and Governors ought to stay out of education policy.

Friday, April 27, 2012

Monday, April 23, 2012

The - Well, ONE - Trouble with Law Finals

It turns out that there are some problems with the law school pedagogical model. I know; try to suppress your shock. There are any number of things I think are genuinely problematic about the standard way law is taught in our law schools: lack of formative assessment, under-inclusion of professional skill building, complete disregard for best learning practices, etc. I suspect that I will write posts on many of these things in the future. But because I've spent I don't know how many days in a row outlining for finals and there's smoke billowing from my ears, I want to hone in specifically on what's wrong with final exams.

Actually, it occurs to me that I need to be even more specific. It's bad pedagogical practice to have only one assessment determine a student's grade, and it's simply frickin' bananas to have it be based on one exam over three hours. Let's call it what it is: crazy.

But those aren't the things I find most crazy about it (at least not at a late hour on a Sunday during finals season). What drives me up the wall the most as a teacher is that students are tested on something they aren't given any formal opportunities to practice once during the year.

What we do as law students is read. We read cases, we take notes, we are very occasionally called upon to discuss those cases in class. We are sometimes exposed to a counterfactual - "Mr. Jakle, would the case have come out differently if X were true instead of Y?" - but we are never asked to examine a fictional fact pattern, analyze the legal questions and write a few thousand words on those angles. Until the final.

I'm not really sure how to convey how truly absurd this is.

"OK, kid: read a ton of cases, be sure to highlight them. Come to class and try not to spend too much time adjusting your fantasy football line-up. Two or three times during these three months, I will spend two minutes asking you about one case and wondering how minor tweaks might make a difference. Study with friends! Or, you know, don't. Mainly just read cases, think about them, and listen to me talk about them. At the end of the semester I will determine your entire grade based on your ability to do none of these things."

We are told all the time that we are being trained to "think like a lawyer." (Seriously, if you aren't a law student ask one how often they're told that). For my colleagues who actually intend to be lawyers, I think it would be more helpful to be trained to just be a lawyer, but I digress. Let me ask you this: if you were teaching someone to be a quarterback, how would you do it?

I'd like to suggest that you would NOT do the following:

Step 1: Show them tape of Joe Montana's greatest moments.

Step 2: Ask questions about how Montana makes decisions in the pocket.

Step 3: Compare how Montana looks at a play and how other quarterbacks operate.

Step 4: Look at a series of pass plays from a playbook.

Step 5: Discuss what a quarterback might do in various situations.

And hey presto! You've got a quarterback course! Oh, here's the kicker: your whole grade will be an exam where you have to go on to a field and throw footballs. Which you've never done before. Ever. Good luck!

Is it just me, or that just an insane way to teach somebody to do something?

One more simile, because I'm feeling punchy. Would you ever, ever, send someone into combat because they had played Halo 3 for 13 weeks? I certainly hope not. And there's a least an argument that playing Halo is a better facsimile of combat that reading case law is of taking a law exam. Except perhaps for the aliens.

It's almost more like showing someone videos of combat, and then showing them how an M-4 is built, and then expecting that that training would make them a competent marksman.

I think one of the reasons I'm struggling to articulate exactly what I think is so misguided about the practice is that - when you break it down - it's so inescapably simple. I dare you to disagree with the following proposition: It's a good idea to practice something you'll be tested on. If you were going to teach someone to swim, and then grade them on their ability to swim, you would - at some point - want them to enter a pool, right? You wouldn't show your students videos of Michael Phelps and Natalie Coughlin, ask them (your students) what was great about their techniques, and then toss them (still your students) into the deep end.

Which is essentially what law professors do. "There are three things you need to fix a car engine: a ratchet, pliers, a screwdriver. Great! Now fix this engine." (If it's not already painfully clear, I have absolutely no idea how to fix an engine.)

I'll stop with the comparisons, and I'll resist the temptation to make this a diatribe on everything I think could be improved about the legal educational model. Instead, I'll just end with this. If you're a law student, consider whether your professors this semester have given you any structured opportunity to practice the specific skill on which you're being tested. I suspect not (if so, good for your professor; they are an exception). If you're not a law student.... well, I guess just relish that fact. And go do this

because you're law student friends aren't.

Actually, it occurs to me that I need to be even more specific. It's bad pedagogical practice to have only one assessment determine a student's grade, and it's simply frickin' bananas to have it be based on one exam over three hours. Let's call it what it is: crazy.

But those aren't the things I find most crazy about it (at least not at a late hour on a Sunday during finals season). What drives me up the wall the most as a teacher is that students are tested on something they aren't given any formal opportunities to practice once during the year.

What we do as law students is read. We read cases, we take notes, we are very occasionally called upon to discuss those cases in class. We are sometimes exposed to a counterfactual - "Mr. Jakle, would the case have come out differently if X were true instead of Y?" - but we are never asked to examine a fictional fact pattern, analyze the legal questions and write a few thousand words on those angles. Until the final.

I'm not really sure how to convey how truly absurd this is.

"OK, kid: read a ton of cases, be sure to highlight them. Come to class and try not to spend too much time adjusting your fantasy football line-up. Two or three times during these three months, I will spend two minutes asking you about one case and wondering how minor tweaks might make a difference. Study with friends! Or, you know, don't. Mainly just read cases, think about them, and listen to me talk about them. At the end of the semester I will determine your entire grade based on your ability to do none of these things."

We are told all the time that we are being trained to "think like a lawyer." (Seriously, if you aren't a law student ask one how often they're told that). For my colleagues who actually intend to be lawyers, I think it would be more helpful to be trained to just be a lawyer, but I digress. Let me ask you this: if you were teaching someone to be a quarterback, how would you do it?

I'd like to suggest that you would NOT do the following:

Step 1: Show them tape of Joe Montana's greatest moments.

Step 2: Ask questions about how Montana makes decisions in the pocket.

Step 3: Compare how Montana looks at a play and how other quarterbacks operate.

Step 4: Look at a series of pass plays from a playbook.

Step 5: Discuss what a quarterback might do in various situations.

And hey presto! You've got a quarterback course! Oh, here's the kicker: your whole grade will be an exam where you have to go on to a field and throw footballs. Which you've never done before. Ever. Good luck!

Is it just me, or that just an insane way to teach somebody to do something?

One more simile, because I'm feeling punchy. Would you ever, ever, send someone into combat because they had played Halo 3 for 13 weeks? I certainly hope not. And there's a least an argument that playing Halo is a better facsimile of combat that reading case law is of taking a law exam. Except perhaps for the aliens.

It's almost more like showing someone videos of combat, and then showing them how an M-4 is built, and then expecting that that training would make them a competent marksman.

I think one of the reasons I'm struggling to articulate exactly what I think is so misguided about the practice is that - when you break it down - it's so inescapably simple. I dare you to disagree with the following proposition: It's a good idea to practice something you'll be tested on. If you were going to teach someone to swim, and then grade them on their ability to swim, you would - at some point - want them to enter a pool, right? You wouldn't show your students videos of Michael Phelps and Natalie Coughlin, ask them (your students) what was great about their techniques, and then toss them (still your students) into the deep end.

Which is essentially what law professors do. "There are three things you need to fix a car engine: a ratchet, pliers, a screwdriver. Great! Now fix this engine." (If it's not already painfully clear, I have absolutely no idea how to fix an engine.)

I'll stop with the comparisons, and I'll resist the temptation to make this a diatribe on everything I think could be improved about the legal educational model. Instead, I'll just end with this. If you're a law student, consider whether your professors this semester have given you any structured opportunity to practice the specific skill on which you're being tested. I suspect not (if so, good for your professor; they are an exception). If you're not a law student.... well, I guess just relish that fact. And go do this

because you're law student friends aren't.

Friday, April 20, 2012

Weekly Round-Up for April 20th

Dahlia Lithwick says Judge Janice Rodgers Brown's latest opinion evinces a wish for 1930's political sensibilities on the right.

What does every President since Taft have in common? A lack of facial hair.

How does government decide who gets Secret Service protection? David Weigel tells us.

And Forrest Wickman wonders why they're always touching their ears.

The Atlantic worries that Facebook is making us lonely.

And Eric Klinenberg says "stop worrying."

Jefferson Morley thinks Kansas Secretary of State Kris Korbach will prevent Romney from making in-roads with Latino voters.

Apparently Americans are more scared of Iran right now than they were of the Soviet Union in 1985.

Petraeus and the CIA are urging Obama to step up drone attacks in Yemen.

Can Robert Bales - killer of 17 Afghan civilians - use PTSD as a defense?

I love this: The Bachelor is facing a class action lawsuit for racial discrimination.

Relatedly, Andrew O'Hehir wonders why rom-coms are still segregated.

Edward Tenner says grammatical rules are changing and you should get over it already.

What does every President since Taft have in common? A lack of facial hair.

How does government decide who gets Secret Service protection? David Weigel tells us.

And Forrest Wickman wonders why they're always touching their ears.

The Atlantic worries that Facebook is making us lonely.

And Eric Klinenberg says "stop worrying."

Jefferson Morley thinks Kansas Secretary of State Kris Korbach will prevent Romney from making in-roads with Latino voters.

Apparently Americans are more scared of Iran right now than they were of the Soviet Union in 1985.

Petraeus and the CIA are urging Obama to step up drone attacks in Yemen.

Can Robert Bales - killer of 17 Afghan civilians - use PTSD as a defense?

I love this: The Bachelor is facing a class action lawsuit for racial discrimination.

Relatedly, Andrew O'Hehir wonders why rom-coms are still segregated.

Edward Tenner says grammatical rules are changing and you should get over it already.

Monday, April 16, 2012

Branch, Jackie, and How Baseball Changed Everything

Yesterday, April 15th, was Jackie Robinson Day, Major League Baseball's annual tribute to a pioneer, a hero, an All-Star, the immortal Number 42. In honor of Jackie and yesterday's memorial, I want to do something a bit different today. The blurb that describes this blog says law leaves its fingerprints all over everything, and that my purpose is to describe the myriad smudges it leaves on our lives without our even realizing. Today, I want to flip the script, because it's a two-way street. The law moulds our lives in all sorts of ways, but so to do we mould the law. There are few better examples of how society affects law than the story of #42.

The standard narrative of the legal demolition of Jim Crow often both begins and culminates with Brown. There's no doubt that Brown was a singular moment in American history, an institutional signal that the status quo was unacceptable and that a sea change in American life was necessary.

But the story of the Warren Court as a heroic bench that grabbed the ropes and tore down inequality is, at best, an over-simplification. It was not the bolt from the blue that many still assume it was; there were murmurs, earlier shakes to the system that indicated what was to come. In a series of cases around 1950, the Court decided that states could not send black students to an out of state law school (Gaines), that group learning was crucial to a Higher Education Doctoral Program and that segregation therefore wasn't acceptable in that context (McLaurin), and that the social connections made in law schools make segregation unacceptable there, as well (Sweatt).

The Justices had already been pulling out some of the legal supports propping up Jim Crow, but they weren't acting alone. When the Court was deciding Sweatt v Painter in 1950, the Truman administration encouraged the Justices to use the opportunity to strike down segregation altogether. Blacks and whites had served together during World War II, forging bonds a return to civil society couldn't break. In 1948, President Truman officially desegregated the military.

After World War II, the Great Migration greatly increased the functional desegregation in the large cities of the north and the west. Polling outside the south showed that most of the country was, in fact, in favor of desegregation. The country - at least outside of the south - was ready. In some ways, the Court was catching up.

But it wasn't just World War II, it wasn't just the Great Migration, it wasn't just time. In 1947, a seminal moment of American history ushered in a new era. On April 15th, 1947, Jackie Robinson wore the uniform of the Brooklyn Dodgers at Ebbets Field, and over 26,000 fans (14,000 of them black) witnessed the most important day in 20th century American sports: baseball's coming of age.

Today it is difficult to remember or imagine baseball's former prominence in the national psyche. Then, it really was the National Pastime. It more accurately echoed Whitman's words:

"Baseball is our game... America's game; has the snap, go, fling, of the American atmosphere - belongs as much to our institutions, fits into them as significantly as our constitutions, our laws: is just as important as the sum total of our historic life."

When baseball was our civic religion, Jackie's presence at second base stamped indelibly on the national consciousness. The Court was packed with baseball fans, and those nine could not help but be aware of the revolution in baseball parks across the country. (Baseball's roots on the Court run deep. Even twenty-five years later baseball reigned; in the middle of an oral argument during the 1973 National League Championship Series, Justice Stewart passed a note to Justice Blackmun "VP Agnew just resigned! Mets 2, Reds 0.")

But it didn't start on April 15, 1947. It started long before that, with Branch Rickey of Duck Run, Ohio.

Ever since his days as the baseball coach at Ohio Wesleyan University, when he had insisted that Tommy Thomas stay in his room with him at a whites-only hotel in South Bend, Rickey had been determined to do his part to end racial injustice. 40 years later, as the General Manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Branch did more than many could have imagined.

A brilliant student, an excellent athlete, a fervent Methodist, and an endless story-teller, Branch Rickey revolutionized baseball not once, not twice, but three times. Best known for bringing in Jackie Robinson, he also developed the modern minor league farm system, and his encouragement of a third Major League paved the way for baseball's expansion in the 1960s. And, in the interests of both pride and full-disclosure, he was my Great-Grandfather.

Rickey had played baseball, coached Ohio Wesleyan, managed the Dodgers, but perhaps as important as anything else, he had been trained as a lawyer at the University of Michigan. The next time you complain about law school's workload, consider that he graduated in five semesters instead of six, and did so while coaching the Wolverine's baseball team.

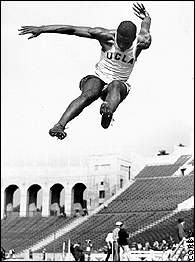

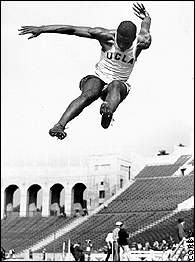

Rickey went about integrating baseball in the same way a civil rights attorney prepares the perfect test case. For one, he had to find the perfect, sympathetic plaintiff. Rickey famously selected Robinson not only for his undeniable athletic gifts - he had been a four-letter athlete at UCLA

but because of his temperament. Knowing the abuse that would be hurled at Robinson in the early days of his playing career, Rickey chose him because - in his words - he "had the courage not to fight back," to turn the other cheek and play the game. A slip would confirm every bigot's belief in the aggressive, uncontrollable black man. Rickey knew his "client" would need an even keel in the batter's box in the same way a lawyer knows his client must control himself on the stand. Robinson was everything he needed to be and more: even-tempered in the face of unimaginable hatred, a success on the diamond despite vicious efforts to injure him, and soon enough a beloved teammate.

Handsome, self possessed; hell, he was even a decorated veteran. He was any lawyer's dream client.

Rickey and Robinson pressed their case before the Court of Public Opinion. Robinson won Rookie of the Year in 1947, and in 1948 Satchel Paige joined Larry Doby on the Cleveland Indians (the first team to integrate in the American League), and three other black athletes joined Jackie on the Dodgers. In 1949, Jackie Robinson was selected to the National League All-Star team not by coaches, not by teammates, but by baseball's fans. Branch and Jackie won their case.

Now, 65 years after Jackie first walked to a Major League plate, I walk the same halls at Michigan Law that my Great-Grandfather walked over a hundred years ago. I am ever aware of the legacy he has left for me, for my fellow law students, and for all of us. I keep the portrait shown above next to my desk as a reminder, as both an exhortation to achievement and a check on my humility. I look for him at Hutchins Hall, imagine him crossing the Law Quad, ponder what answer he might give to a cold call. I take this April 15th as a reminder to keep him with me.

I encourage you to take some time today to think about the changes these men wrought on our world. Do not forget that just as our laws shape us, so do we shape our laws. Never underestimate the power of sports to heal our wounds, to hold a mirror up to our society and show both its finer features and its blemishes. Always remember that grace in the face of hatred and vitriol is both the more difficult and the more rewarding path. Above all, never, never forget that even just two people can - through work, belief, and determination of will - change the face of a nation.

]

]

Happy Jackie Robinson Day.

The standard narrative of the legal demolition of Jim Crow often both begins and culminates with Brown. There's no doubt that Brown was a singular moment in American history, an institutional signal that the status quo was unacceptable and that a sea change in American life was necessary.

But the story of the Warren Court as a heroic bench that grabbed the ropes and tore down inequality is, at best, an over-simplification. It was not the bolt from the blue that many still assume it was; there were murmurs, earlier shakes to the system that indicated what was to come. In a series of cases around 1950, the Court decided that states could not send black students to an out of state law school (Gaines), that group learning was crucial to a Higher Education Doctoral Program and that segregation therefore wasn't acceptable in that context (McLaurin), and that the social connections made in law schools make segregation unacceptable there, as well (Sweatt).

The Justices had already been pulling out some of the legal supports propping up Jim Crow, but they weren't acting alone. When the Court was deciding Sweatt v Painter in 1950, the Truman administration encouraged the Justices to use the opportunity to strike down segregation altogether. Blacks and whites had served together during World War II, forging bonds a return to civil society couldn't break. In 1948, President Truman officially desegregated the military.

After World War II, the Great Migration greatly increased the functional desegregation in the large cities of the north and the west. Polling outside the south showed that most of the country was, in fact, in favor of desegregation. The country - at least outside of the south - was ready. In some ways, the Court was catching up.

But it wasn't just World War II, it wasn't just the Great Migration, it wasn't just time. In 1947, a seminal moment of American history ushered in a new era. On April 15th, 1947, Jackie Robinson wore the uniform of the Brooklyn Dodgers at Ebbets Field, and over 26,000 fans (14,000 of them black) witnessed the most important day in 20th century American sports: baseball's coming of age.

Today it is difficult to remember or imagine baseball's former prominence in the national psyche. Then, it really was the National Pastime. It more accurately echoed Whitman's words:

"Baseball is our game... America's game; has the snap, go, fling, of the American atmosphere - belongs as much to our institutions, fits into them as significantly as our constitutions, our laws: is just as important as the sum total of our historic life."

When baseball was our civic religion, Jackie's presence at second base stamped indelibly on the national consciousness. The Court was packed with baseball fans, and those nine could not help but be aware of the revolution in baseball parks across the country. (Baseball's roots on the Court run deep. Even twenty-five years later baseball reigned; in the middle of an oral argument during the 1973 National League Championship Series, Justice Stewart passed a note to Justice Blackmun "VP Agnew just resigned! Mets 2, Reds 0.")

But it didn't start on April 15, 1947. It started long before that, with Branch Rickey of Duck Run, Ohio.

Ever since his days as the baseball coach at Ohio Wesleyan University, when he had insisted that Tommy Thomas stay in his room with him at a whites-only hotel in South Bend, Rickey had been determined to do his part to end racial injustice. 40 years later, as the General Manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Branch did more than many could have imagined.

A brilliant student, an excellent athlete, a fervent Methodist, and an endless story-teller, Branch Rickey revolutionized baseball not once, not twice, but three times. Best known for bringing in Jackie Robinson, he also developed the modern minor league farm system, and his encouragement of a third Major League paved the way for baseball's expansion in the 1960s. And, in the interests of both pride and full-disclosure, he was my Great-Grandfather.

Rickey had played baseball, coached Ohio Wesleyan, managed the Dodgers, but perhaps as important as anything else, he had been trained as a lawyer at the University of Michigan. The next time you complain about law school's workload, consider that he graduated in five semesters instead of six, and did so while coaching the Wolverine's baseball team.

Rickey went about integrating baseball in the same way a civil rights attorney prepares the perfect test case. For one, he had to find the perfect, sympathetic plaintiff. Rickey famously selected Robinson not only for his undeniable athletic gifts - he had been a four-letter athlete at UCLA

but because of his temperament. Knowing the abuse that would be hurled at Robinson in the early days of his playing career, Rickey chose him because - in his words - he "had the courage not to fight back," to turn the other cheek and play the game. A slip would confirm every bigot's belief in the aggressive, uncontrollable black man. Rickey knew his "client" would need an even keel in the batter's box in the same way a lawyer knows his client must control himself on the stand. Robinson was everything he needed to be and more: even-tempered in the face of unimaginable hatred, a success on the diamond despite vicious efforts to injure him, and soon enough a beloved teammate.

Handsome, self possessed; hell, he was even a decorated veteran. He was any lawyer's dream client.

Rickey and Robinson pressed their case before the Court of Public Opinion. Robinson won Rookie of the Year in 1947, and in 1948 Satchel Paige joined Larry Doby on the Cleveland Indians (the first team to integrate in the American League), and three other black athletes joined Jackie on the Dodgers. In 1949, Jackie Robinson was selected to the National League All-Star team not by coaches, not by teammates, but by baseball's fans. Branch and Jackie won their case.

Now, 65 years after Jackie first walked to a Major League plate, I walk the same halls at Michigan Law that my Great-Grandfather walked over a hundred years ago. I am ever aware of the legacy he has left for me, for my fellow law students, and for all of us. I keep the portrait shown above next to my desk as a reminder, as both an exhortation to achievement and a check on my humility. I look for him at Hutchins Hall, imagine him crossing the Law Quad, ponder what answer he might give to a cold call. I take this April 15th as a reminder to keep him with me.

I encourage you to take some time today to think about the changes these men wrought on our world. Do not forget that just as our laws shape us, so do we shape our laws. Never underestimate the power of sports to heal our wounds, to hold a mirror up to our society and show both its finer features and its blemishes. Always remember that grace in the face of hatred and vitriol is both the more difficult and the more rewarding path. Above all, never, never forget that even just two people can - through work, belief, and determination of will - change the face of a nation.

]

]Happy Jackie Robinson Day.

Friday, April 13, 2012

Weekly Round-Up for April 13th

This week's best and most interesting stories:

The New York Times reports on the second-degree murder charges against George Zimmermann.

Joan Walsh at Salon says it wouldn't have happened with the social movement that followed the killing.

David Wiegel on how Trayvon Martin's killing is affecting the Florida election.

Emily Bazelon tells us why we should be shocked about George Zimmermann's lawyer's behavior.

At the Times, a story on how the NRA has advanced laws like Florida's.

Obama has declined to ban anti-gay discrimination by employers with Federal contracts.

Salon reports that declining abortion options in the South indicate a triumph of society over law.

For those of you unsure, Andrew Leonard explains the so-called "Buffet Rule."

Salon interviews Faramerz Dabhoiwala, author of "The Origins of Sex," and he talks about altering social norms and expectations in the 1760s.

Tracy Clark-Flory examines the new UK tv-show "Dating while Disabled." Progressive? Exploitative?

Transgender contestants can now compete on "Miss Universe," thanks to... Donald Trump?!

An investigation into the pepper spraying at UC Davis last fall finds fault with the Chancellor.

The New York Times reports on the second-degree murder charges against George Zimmermann.

Joan Walsh at Salon says it wouldn't have happened with the social movement that followed the killing.

David Wiegel on how Trayvon Martin's killing is affecting the Florida election.

Emily Bazelon tells us why we should be shocked about George Zimmermann's lawyer's behavior.

At the Times, a story on how the NRA has advanced laws like Florida's.

Obama has declined to ban anti-gay discrimination by employers with Federal contracts.

Salon reports that declining abortion options in the South indicate a triumph of society over law.

For those of you unsure, Andrew Leonard explains the so-called "Buffet Rule."

Salon interviews Faramerz Dabhoiwala, author of "The Origins of Sex," and he talks about altering social norms and expectations in the 1760s.

Tracy Clark-Flory examines the new UK tv-show "Dating while Disabled." Progressive? Exploitative?

Transgender contestants can now compete on "Miss Universe," thanks to... Donald Trump?!

An investigation into the pepper spraying at UC Davis last fall finds fault with the Chancellor.

Thursday, April 12, 2012

A Moving Piece of History

A remarkable video of a Cambridge debate between two undergraduates, James Baldwin, and William F Buckley, Jr. The undergraduate's elocution is undeniable, and WFB Jrs use of words as a rapier unmatched, but it's most notable for James Baldwin's beautiful, moving speech. It's a fascinating hour of television, and I recommend the whole thing, but at least be sure to watch Baldwin.

For those who want to cherry pick:

First undergraduate: 3:15 of Part 1 to 8:08 Part 1

Second undergraduate: 8:29 of Part 1 to 3:47 of Part 2

James Baldwin: 4:15 of Part 2 to 8:05 of Part 4

WFB: 9:35 of Part 4 to 7:57 of Part 6

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

For those who want to cherry pick:

First undergraduate: 3:15 of Part 1 to 8:08 Part 1

Second undergraduate: 8:29 of Part 1 to 3:47 of Part 2

James Baldwin: 4:15 of Part 2 to 8:05 of Part 4

WFB: 9:35 of Part 4 to 7:57 of Part 6

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

Monday, April 9, 2012

Prose on Rituals' Pros

The week after Passover/Easter weekend seems like as apt a time as any to talk about the importance of tradition and ritual. I'm not a religious person myself, but I'm coming more and more to realize that you don't need to be religious to understand that ritual can play a very important role for us. Alain de Botton put it quite nicely:

"It's really important to look at the moon. When you look at the moon, you think 'I'm really small. What are my problems?' It set things into perspective. We should all look at the moon a bit more often, but we don't. Why don't we? There's nothing to tell us 'Look at the moon.' But if you're a Zen Buddhist in the middle of September, you will be ordered out of your home, made to stand on a canonical platform, and made to celebrate the Festival of Tsukimi, where you will be given poems to read in honor of the moon and the passage of time, and the frailty of life that it reminds us of."

There's a lot that doesn't come naturally to a lot of us that's worth being reminded of time to time: that we depend on others, that our community needs us just as we need it, that we should be thankful for what we have, that we should work hard and do our duty to others. It's so easy to lose sight of this, to get wrapped up in our own day to day needs. I found Saturday's Seder to be a nice reminder not only of how lucky I am to have have the options that I do, but that those reminders are important.

It got me thinking about the rituals and the law. It's a massive topic. For a long time, the law was essentially a series of rituals.

(The picture is of trial by ordeal, fyi).

To limit the discussion, I just want to make two points. First, ritual and tradition structure our ideas of what's "normal," and therefore of what courses of conduct are acceptable independent of what the law dictates. Second - and more in line with today's focus - I want to think about rituals that mark the legal process and what they tell us about it.

Quickly though, I'll just give two examples of how a ritual or tradition runs up against formal law. They're admittedly obvious and well-trodden, but here goes. First, let's talk about drinking. Sure, it's most often considered a fun, recreational activity that one occasionally regrets the following day. But mull over how often ritual is involved with drinking: raising a glass, drinking to someone's success, pouring one out. I mean, the Eucharist, for goodness' sake. Even the simple act of going for a drink has become a ritual in both our platonic and dating lives. "I haven't seen you in forever! Let's get a drink soon!" "Listen, I know we only just met, but you seem really cool and I've laughed a lot during this chat. Let me buy a drink this week."

Ever do a shot all by yourself? Hopefully not often. It's something you do with others; its a social ritual. And it turns out that when something like that is woven that deeply into our social fabric, it's really hard to unweave. So banning drinking entirely

doesn't work that well, not simply because we like to drink, but because drinking together is a ritual and tradition deeply embedded in our culture. Oh, and by the way, it banning it leads to this:

Examples like this abound in case law. Native American use of peyote doesn't have the cultural momentum in this country that drinking does, so when the court decided in the 90s that the law needn't make an exception for religious use of peyote, there wasn't the same outlandish backlash as there was after the 18th Amendment. That said, I'll make two bets with you: the first is that those who observe the religious use of peyote wouldn't consider it "wrong" to break the laws to follow ritualistic teachings. Second, I'll bet you no small number of observers still use it.

Incidentally, the peyote ritual is intended to allow the participant to forget him or herself and bond with a higher being. So it serves much the same purpose as a Seder, or the Festival of Tsukimi. You remind yourself of the world beyond yourself.

We have a great many rituals in law. Judicial robes, for instance; what is their ritualistic purpose? By donning uniforms, we have a visual reminder of what our role is, of what function we are supposed to be performing. The number of chevrons on our shoulders reminds others of what respect they are supposed to show us

but it also reminds us of what our duties towards others are supposed to be. Putting on regalia or ceremonial dress reminds us of what function we are supposed to be performing. So when a judge puts on his or her robes, it serves as a reminder that they sit in judgment not as an individual, not as themselves, but as a particular embodiment of the law.

Given that perception, or that ritualized reality, the command "all rise" takes on a special meaning. We aren't rising to respect the entrance of an individual, no matter how accomplished. We rise to witness and respect the entrance of the law, of the embodiment of impartial justice.

Other rituals abound. The reading of one's Miranda rights serves an instrumental (and legally required...) purpose, but it certainly fits the bill of a ritual more generally. It's a commanded act that reminds both the speaker and the listener of certain important realities. Just as the festival of Tsukimi reminds all participants of their places in the universe, Miranda rights remind everyone involved of their places in the legal system.

I'll wrap up with this. No one's perfect. No one can carry with them all the purposes of their obligations. No one can think of others all the time, no one can remember to put others before them every time it's required. These flaws, these imperfections, are not indicia of failure. Rather, they are the very reasons that we need ritual, that we need systematized reminders of what's important, of what we are supposed to do. In law, we see labels applied a lot: victim, perp, prosecutor, judge, accused, defendant, plaintiff, judge, juror. Each of these has a special set of entitlements and duties that come with it. It's okay if we need reminders for life's stranger, more confusing, more complex, more unusual roles.

"It's really important to look at the moon. When you look at the moon, you think 'I'm really small. What are my problems?' It set things into perspective. We should all look at the moon a bit more often, but we don't. Why don't we? There's nothing to tell us 'Look at the moon.' But if you're a Zen Buddhist in the middle of September, you will be ordered out of your home, made to stand on a canonical platform, and made to celebrate the Festival of Tsukimi, where you will be given poems to read in honor of the moon and the passage of time, and the frailty of life that it reminds us of."

There's a lot that doesn't come naturally to a lot of us that's worth being reminded of time to time: that we depend on others, that our community needs us just as we need it, that we should be thankful for what we have, that we should work hard and do our duty to others. It's so easy to lose sight of this, to get wrapped up in our own day to day needs. I found Saturday's Seder to be a nice reminder not only of how lucky I am to have have the options that I do, but that those reminders are important.

It got me thinking about the rituals and the law. It's a massive topic. For a long time, the law was essentially a series of rituals.

(The picture is of trial by ordeal, fyi).

To limit the discussion, I just want to make two points. First, ritual and tradition structure our ideas of what's "normal," and therefore of what courses of conduct are acceptable independent of what the law dictates. Second - and more in line with today's focus - I want to think about rituals that mark the legal process and what they tell us about it.

Quickly though, I'll just give two examples of how a ritual or tradition runs up against formal law. They're admittedly obvious and well-trodden, but here goes. First, let's talk about drinking. Sure, it's most often considered a fun, recreational activity that one occasionally regrets the following day. But mull over how often ritual is involved with drinking: raising a glass, drinking to someone's success, pouring one out. I mean, the Eucharist, for goodness' sake. Even the simple act of going for a drink has become a ritual in both our platonic and dating lives. "I haven't seen you in forever! Let's get a drink soon!" "Listen, I know we only just met, but you seem really cool and I've laughed a lot during this chat. Let me buy a drink this week."

Ever do a shot all by yourself? Hopefully not often. It's something you do with others; its a social ritual. And it turns out that when something like that is woven that deeply into our social fabric, it's really hard to unweave. So banning drinking entirely

doesn't work that well, not simply because we like to drink, but because drinking together is a ritual and tradition deeply embedded in our culture. Oh, and by the way, it banning it leads to this:

Examples like this abound in case law. Native American use of peyote doesn't have the cultural momentum in this country that drinking does, so when the court decided in the 90s that the law needn't make an exception for religious use of peyote, there wasn't the same outlandish backlash as there was after the 18th Amendment. That said, I'll make two bets with you: the first is that those who observe the religious use of peyote wouldn't consider it "wrong" to break the laws to follow ritualistic teachings. Second, I'll bet you no small number of observers still use it.

Incidentally, the peyote ritual is intended to allow the participant to forget him or herself and bond with a higher being. So it serves much the same purpose as a Seder, or the Festival of Tsukimi. You remind yourself of the world beyond yourself.

We have a great many rituals in law. Judicial robes, for instance; what is their ritualistic purpose? By donning uniforms, we have a visual reminder of what our role is, of what function we are supposed to be performing. The number of chevrons on our shoulders reminds others of what respect they are supposed to show us

but it also reminds us of what our duties towards others are supposed to be. Putting on regalia or ceremonial dress reminds us of what function we are supposed to be performing. So when a judge puts on his or her robes, it serves as a reminder that they sit in judgment not as an individual, not as themselves, but as a particular embodiment of the law.

Given that perception, or that ritualized reality, the command "all rise" takes on a special meaning. We aren't rising to respect the entrance of an individual, no matter how accomplished. We rise to witness and respect the entrance of the law, of the embodiment of impartial justice.

Other rituals abound. The reading of one's Miranda rights serves an instrumental (and legally required...) purpose, but it certainly fits the bill of a ritual more generally. It's a commanded act that reminds both the speaker and the listener of certain important realities. Just as the festival of Tsukimi reminds all participants of their places in the universe, Miranda rights remind everyone involved of their places in the legal system.

I'll wrap up with this. No one's perfect. No one can carry with them all the purposes of their obligations. No one can think of others all the time, no one can remember to put others before them every time it's required. These flaws, these imperfections, are not indicia of failure. Rather, they are the very reasons that we need ritual, that we need systematized reminders of what's important, of what we are supposed to do. In law, we see labels applied a lot: victim, perp, prosecutor, judge, accused, defendant, plaintiff, judge, juror. Each of these has a special set of entitlements and duties that come with it. It's okay if we need reminders for life's stranger, more confusing, more complex, more unusual roles.

Friday, April 6, 2012

Weekly Round-Up for April 6

As always, some of the week's best and most interesting stories:

Eliot Spitzer warns conservatives not to get their hopes up too high about the Affordable Care Act.

Emily Bazelon discusses the evidence that might (or might not) be admissible against George Zimmerman if there were a trial.

A new legal challenge to the Defense of Marriage Act from non-citizens about spousal green cards.

Joan Walsh links conservative social policy to anxiety about gender roles and the "traditional" family.

How many land use covenants, ordinances, or zoning regulations might come in to play in housing communities modeled after old European neighborhoods?

At Salon, Michael Gould-Wartofsky talks about Trayvon Martin and our vigilante history.

Andrew Leonard on how law and politics will affect student loan burdens.

Derek Thompson at the Atlantic writes a really interesting piece on how the American family's spending habits have changed over the last century.

Eliot Spitzer warns conservatives not to get their hopes up too high about the Affordable Care Act.

Emily Bazelon discusses the evidence that might (or might not) be admissible against George Zimmerman if there were a trial.

A new legal challenge to the Defense of Marriage Act from non-citizens about spousal green cards.

Joan Walsh links conservative social policy to anxiety about gender roles and the "traditional" family.

How many land use covenants, ordinances, or zoning regulations might come in to play in housing communities modeled after old European neighborhoods?

At Salon, Michael Gould-Wartofsky talks about Trayvon Martin and our vigilante history.

Andrew Leonard on how law and politics will affect student loan burdens.

Derek Thompson at the Atlantic writes a really interesting piece on how the American family's spending habits have changed over the last century.

Monday, April 2, 2012

What Judge Judy Tells Us About the Healthcare Case

I thought long and hard about whether I had anything interesting to say about the healthcare hearings last week, whether I could say anything new or different about the Affordable Care Act, about the role of government in our lives, or about the political battle lines drawn around rampant misinformation about what "Obamacare" actually entails.

Yeah... probably not.

But something interesting did happen: the nation's whole commetariat became obsessed with a case that's not (primarily) about abortion. We usually reserve the attention we gave the Court last week for Roe type cases, not cases that begin with two hours of hearings about the Anti-Injuction Act of 1875. The media firestorm came with its own curiosity: with all the talk about the length of the hearings and the quick turnaround of the audio tapes, no one - or at least almost no one on TV, in print, or on the internet - asked "why not live audio?" or "why not video?"

I talked about this with a few folks, but only in passing. One friend's students expressed a worry that it would make the Supreme Court too much like this:

Now, I think there'a lot more than video standing between Judge Judy and the Supreme Court of the United States. For one, Judge Judy isn't a judge. She was (in New York State Criminal Courts from 1982-1996), but she isn't anymore; her decisions on TV are only enforceable because the "litigants" sign binding arbitration agreements. She's an arbitrator, but I have to acknowledge that "Arbitrator Judy" doesn't have nearly the same ring to it.

But it does make me wonder why we think putting the Supreme Court on TV would somehow cheapen it. We have televised looks into the other branches: Presidential addresses, news coverage, C-SPAN generally. What makes the Court special?

I think it's because we want to pretend that the boundary between law and politics is starker and better defended that it actually is. In order to see the Supreme Court, you literally have to ascend to upon high. You must climb the high marble steps, walk between those impressive pillars. The building is constructed as a temple of justice.

So, to, are the Capitol building and the White House, but we don't actually have to ascend to witness the goings on. They can be brought into our homes, our living rooms, and maybe this makes them seem more mundane. If we could watch Scalia read an opinion from the bench, maybe it would lose whatever mysticism seems to attach to it. Opinions are "handed down," taking on a air of decrees from on high. I think maybe humanizing the Court would rob it of its majesty.

This let's us keep thinking that law isn't simply politics continued by other means. Don't get me wrong, I think there is some content to law that isn't simply captured by politics. But ironically, this is less true at the Supreme Court than almost anywhere else. Cases make it there because they don't have clear legal answers, because they contain questions on which reasonable people can disagree and for which there is no clear "right" answer. If there were, it would have been dispensed with at a lower court and its appeals rejected. Politics plays a bigger role in SCOTUS decisions than almost anywhere else in the law. This troubles us, I think, and treating it differently than other branches let's us pretend it's less true.

For similar reasons, we don't want to worry that the judges worry about their perception, how they sound on tape, how they look on camera, whether they look tiny in a big wooden chair, etc.

Whether we really believe it or not, some part of us seems comforted by the idea that nine wise persons sit in high-minded judgment, unimpeded by thoughts of anything other than their love and knowledge of the law.

I mean, that's a load, but I understand why we feel comforted by it. We don't want our Justices to resemble this guy:

So, for the first time since I started writing on this page, let me ask you: why does increasing access to the Supreme Court feel wrong, or cheap? Or am I wrong in thinking that they are? I'm really curious to hear what you think: do we lionize the Court more than we should, or are their good reasons for the reverence these practices are designed to inculcate?

Yeah... probably not.

But something interesting did happen: the nation's whole commetariat became obsessed with a case that's not (primarily) about abortion. We usually reserve the attention we gave the Court last week for Roe type cases, not cases that begin with two hours of hearings about the Anti-Injuction Act of 1875. The media firestorm came with its own curiosity: with all the talk about the length of the hearings and the quick turnaround of the audio tapes, no one - or at least almost no one on TV, in print, or on the internet - asked "why not live audio?" or "why not video?"

I talked about this with a few folks, but only in passing. One friend's students expressed a worry that it would make the Supreme Court too much like this:

Now, I think there'a lot more than video standing between Judge Judy and the Supreme Court of the United States. For one, Judge Judy isn't a judge. She was (in New York State Criminal Courts from 1982-1996), but she isn't anymore; her decisions on TV are only enforceable because the "litigants" sign binding arbitration agreements. She's an arbitrator, but I have to acknowledge that "Arbitrator Judy" doesn't have nearly the same ring to it.

But it does make me wonder why we think putting the Supreme Court on TV would somehow cheapen it. We have televised looks into the other branches: Presidential addresses, news coverage, C-SPAN generally. What makes the Court special?

I think it's because we want to pretend that the boundary between law and politics is starker and better defended that it actually is. In order to see the Supreme Court, you literally have to ascend to upon high. You must climb the high marble steps, walk between those impressive pillars. The building is constructed as a temple of justice.

So, to, are the Capitol building and the White House, but we don't actually have to ascend to witness the goings on. They can be brought into our homes, our living rooms, and maybe this makes them seem more mundane. If we could watch Scalia read an opinion from the bench, maybe it would lose whatever mysticism seems to attach to it. Opinions are "handed down," taking on a air of decrees from on high. I think maybe humanizing the Court would rob it of its majesty.

This let's us keep thinking that law isn't simply politics continued by other means. Don't get me wrong, I think there is some content to law that isn't simply captured by politics. But ironically, this is less true at the Supreme Court than almost anywhere else. Cases make it there because they don't have clear legal answers, because they contain questions on which reasonable people can disagree and for which there is no clear "right" answer. If there were, it would have been dispensed with at a lower court and its appeals rejected. Politics plays a bigger role in SCOTUS decisions than almost anywhere else in the law. This troubles us, I think, and treating it differently than other branches let's us pretend it's less true.

For similar reasons, we don't want to worry that the judges worry about their perception, how they sound on tape, how they look on camera, whether they look tiny in a big wooden chair, etc.

Whether we really believe it or not, some part of us seems comforted by the idea that nine wise persons sit in high-minded judgment, unimpeded by thoughts of anything other than their love and knowledge of the law.

I mean, that's a load, but I understand why we feel comforted by it. We don't want our Justices to resemble this guy:

So, for the first time since I started writing on this page, let me ask you: why does increasing access to the Supreme Court feel wrong, or cheap? Or am I wrong in thinking that they are? I'm really curious to hear what you think: do we lionize the Court more than we should, or are their good reasons for the reverence these practices are designed to inculcate?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)