The standard narrative of the legal demolition of Jim Crow often both begins and culminates with Brown. There's no doubt that Brown was a singular moment in American history, an institutional signal that the status quo was unacceptable and that a sea change in American life was necessary.

But the story of the Warren Court as a heroic bench that grabbed the ropes and tore down inequality is, at best, an over-simplification. It was not the bolt from the blue that many still assume it was; there were murmurs, earlier shakes to the system that indicated what was to come. In a series of cases around 1950, the Court decided that states could not send black students to an out of state law school (Gaines), that group learning was crucial to a Higher Education Doctoral Program and that segregation therefore wasn't acceptable in that context (McLaurin), and that the social connections made in law schools make segregation unacceptable there, as well (Sweatt).

The Justices had already been pulling out some of the legal supports propping up Jim Crow, but they weren't acting alone. When the Court was deciding Sweatt v Painter in 1950, the Truman administration encouraged the Justices to use the opportunity to strike down segregation altogether. Blacks and whites had served together during World War II, forging bonds a return to civil society couldn't break. In 1948, President Truman officially desegregated the military.

After World War II, the Great Migration greatly increased the functional desegregation in the large cities of the north and the west. Polling outside the south showed that most of the country was, in fact, in favor of desegregation. The country - at least outside of the south - was ready. In some ways, the Court was catching up.

But it wasn't just World War II, it wasn't just the Great Migration, it wasn't just time. In 1947, a seminal moment of American history ushered in a new era. On April 15th, 1947, Jackie Robinson wore the uniform of the Brooklyn Dodgers at Ebbets Field, and over 26,000 fans (14,000 of them black) witnessed the most important day in 20th century American sports: baseball's coming of age.

Today it is difficult to remember or imagine baseball's former prominence in the national psyche. Then, it really was the National Pastime. It more accurately echoed Whitman's words:

"Baseball is our game... America's game; has the snap, go, fling, of the American atmosphere - belongs as much to our institutions, fits into them as significantly as our constitutions, our laws: is just as important as the sum total of our historic life."

When baseball was our civic religion, Jackie's presence at second base stamped indelibly on the national consciousness. The Court was packed with baseball fans, and those nine could not help but be aware of the revolution in baseball parks across the country. (Baseball's roots on the Court run deep. Even twenty-five years later baseball reigned; in the middle of an oral argument during the 1973 National League Championship Series, Justice Stewart passed a note to Justice Blackmun "VP Agnew just resigned! Mets 2, Reds 0.")

But it didn't start on April 15, 1947. It started long before that, with Branch Rickey of Duck Run, Ohio.

Ever since his days as the baseball coach at Ohio Wesleyan University, when he had insisted that Tommy Thomas stay in his room with him at a whites-only hotel in South Bend, Rickey had been determined to do his part to end racial injustice. 40 years later, as the General Manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Branch did more than many could have imagined.

A brilliant student, an excellent athlete, a fervent Methodist, and an endless story-teller, Branch Rickey revolutionized baseball not once, not twice, but three times. Best known for bringing in Jackie Robinson, he also developed the modern minor league farm system, and his encouragement of a third Major League paved the way for baseball's expansion in the 1960s. And, in the interests of both pride and full-disclosure, he was my Great-Grandfather.

Rickey had played baseball, coached Ohio Wesleyan, managed the Dodgers, but perhaps as important as anything else, he had been trained as a lawyer at the University of Michigan. The next time you complain about law school's workload, consider that he graduated in five semesters instead of six, and did so while coaching the Wolverine's baseball team.

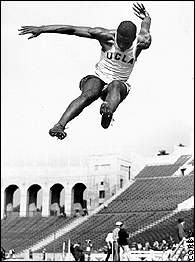

Rickey went about integrating baseball in the same way a civil rights attorney prepares the perfect test case. For one, he had to find the perfect, sympathetic plaintiff. Rickey famously selected Robinson not only for his undeniable athletic gifts - he had been a four-letter athlete at UCLA

but because of his temperament. Knowing the abuse that would be hurled at Robinson in the early days of his playing career, Rickey chose him because - in his words - he "had the courage not to fight back," to turn the other cheek and play the game. A slip would confirm every bigot's belief in the aggressive, uncontrollable black man. Rickey knew his "client" would need an even keel in the batter's box in the same way a lawyer knows his client must control himself on the stand. Robinson was everything he needed to be and more: even-tempered in the face of unimaginable hatred, a success on the diamond despite vicious efforts to injure him, and soon enough a beloved teammate.

Handsome, self possessed; hell, he was even a decorated veteran. He was any lawyer's dream client.

Rickey and Robinson pressed their case before the Court of Public Opinion. Robinson won Rookie of the Year in 1947, and in 1948 Satchel Paige joined Larry Doby on the Cleveland Indians (the first team to integrate in the American League), and three other black athletes joined Jackie on the Dodgers. In 1949, Jackie Robinson was selected to the National League All-Star team not by coaches, not by teammates, but by baseball's fans. Branch and Jackie won their case.

Now, 65 years after Jackie first walked to a Major League plate, I walk the same halls at Michigan Law that my Great-Grandfather walked over a hundred years ago. I am ever aware of the legacy he has left for me, for my fellow law students, and for all of us. I keep the portrait shown above next to my desk as a reminder, as both an exhortation to achievement and a check on my humility. I look for him at Hutchins Hall, imagine him crossing the Law Quad, ponder what answer he might give to a cold call. I take this April 15th as a reminder to keep him with me.

I encourage you to take some time today to think about the changes these men wrought on our world. Do not forget that just as our laws shape us, so do we shape our laws. Never underestimate the power of sports to heal our wounds, to hold a mirror up to our society and show both its finer features and its blemishes. Always remember that grace in the face of hatred and vitriol is both the more difficult and the more rewarding path. Above all, never, never forget that even just two people can - through work, belief, and determination of will - change the face of a nation.

]

]Happy Jackie Robinson Day.

what a great post!! happy belated JRD!!

ReplyDeleteOh, okay, so THAT's how you decided to go to Michigan. Awesome, awesome post!

ReplyDelete