The week's links:

Richard Hasen says modern campaign corruption makes Nixon look like a nun (or something to that effect): Worse than Watergate

The final (I think?) installment of Slate's Constitution series: We the People of Slate ...

Breaking news, everyone, Michelle Bachmann is a raving loon:Bachmann’s Grotesque Attack on Clinton Aide Huma Abedin, Bachmann Hunts for Traitorous Muslims; McCain Shames Her, Michele Bachmann’s hateful cronies, Rubio condemns Bachmann, Why Bachmann’s witch hunt matters, Michele Bachmann under fire from Keith Ellison, John McCain, Bachmann defends her witch hunt

Virginia, seriously, calm down with this stuff: Another Abortion Showdown in Virginia

Also, come on, Arizona: What Arizona’s abortion ban means for Roe v. Wade

Some interesting stuff on marijuana this week: Obama’s pot problem, If Pot Were Truly Legal, Joints Would Cost Only a Few Cents

From the Chronicle: Federal Student-Visa Program Is Vulnerable to Fraud, Report Says

Thursday, July 19, 2012

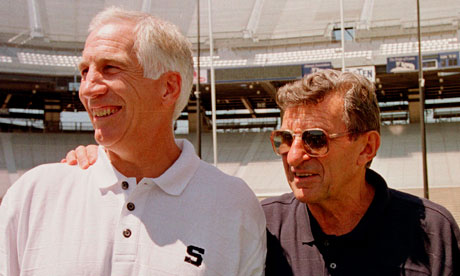

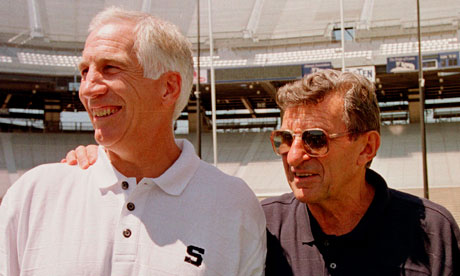

The Anti Penn State Scandal

From a friend of the blog, an antidote to the continuing horror at Penn State: Caltech has self-reported that not all of it's athletes were taking full course loads at the time of competition. They have voluntarily vacated, to pick one example, all of the wins their baseball team had during a time they went 0-112, and all the Ws from water polo's 0-66 run. I am not making this up.

It's mens basketball win over Occidental will stand.

More coverage at the LA Times: Bill Plaschke: No pi on Caltech's face for NCAA probation. - Los Angeles Times

It's mens basketball win over Occidental will stand.

More coverage at the LA Times: Bill Plaschke: No pi on Caltech's face for NCAA probation. - Los Angeles Times

Monday, July 16, 2012

Count to 45

The Penn State tragedy is the biggest scandal in the history of college sports. I exaggerate sometimes; it runs in the family. Sometimes a story needs just a little touch-up, a little embellishment to catch in your audience. The reason I want you to know I'm aware of this is so I can tell you I'm dead serious.

The Penn State tragedy is the biggest scandal in the history of college sports, and it's not even close.

Some numbers to try on for size:

45: the number of felonious sexual assaults for which Jerry Sandusky was convicted. Try counting all the way to 45 knowing that each number represents the horrific rape of a child. I bet you don't make it. Maybe you can make it to:

8: the number of children whose lives were torn open by those 45 crimes.

4: the (minimum) number of senior University officials who knew about Sandusky's pestilent predilections. President Spanier, VP Schultz, AD Curley and CEO Pope Don Coach Paterno. These four men knew - knew that Sandusky was raping children - and did nothing. Well, nothing but actively cover it up as it continued to happen.

14: the number of years those men knew about those crimes but kept silent as the horror continued.

The president of a University stayed silent for fourteen years to cover up the unspeakable acts of a former football coach. Even as I type it I can barely believe it's true. The depth of institutional failure is horrifying, mind-numbing. The so-called "Culture of Reverence" for the football team at State College insulated a child rapist from the law for almost a decade and a half. Joe Paterno built a legend on the idea that you could win with integrity; the Grand Experiment was premised on the notion that you could carry yourselves on and off the field as true student-athletes, and that you would burnish - not tarnish - your school and its academic standards through deeds on the gridiron.

It sounds like a sick joke, now; now that we know Joe Paterno - the most powerful man at Penn State, to be sure - knew that his colleague was involved in the serial rape of children from at least 1998 to the day he died, and lied about it to all of us. As alum Michael Weinreb wrote over at Grantland, "the Grand Experiment is a failure, and the entire laboratory is contaminated, and there is no choice to go back and start all over again.

So I'm joining the throng of writers urging Penn State to suspend its football program. Shut it down. Turn off the lights. Pull back the culture of reverence that enabled this whole disaster.

I know the counterarguments: shuttering Penn State football will do nothing to punish the four men who participated in this grotesque cover-up. They all lost their jobs, one's dead, and the other three are facing criminal charges (or will soon). Shutting down football doesn't hurt them, it hurts the current players, current students, and current administrators who didn't do anything wrong.

I can hear some of you saying right now, "those students didn't do anything wrong, and suspending football will not only deprive them of the entertainment, but of the astronomical publicity, prestige and cash that it brings in." And you're right, turning off Nittany Lion football would be a crushing blow to the institution, but that's the whole problem. When eliminating a football team is the biggest single blow you can aim at an institution, the football team is plain and simply too damn important. It's that level of institutional dependence on a sport that led four allegedly upstanding members of the Penn State community to prioritize it over the lives of children.

Which, by the way, is why we're kidding ourselves when we say this was a one off thing that couldn't have happened anywhere else. I like to think that at schools like Texas, Florida, Alabama, Nebraska, USC, Oklahoma, LSU, Ohio State, and my beloved Michigan someone would have blown the whistle and reported Sandusky's crimes, instead of doing what Penn State did - take away his key to the locker room showers. But at each of those schools, football is God. The Michigan Winged Helmet is the most important and visible symbol of the university, Alabama's Crimson Tide is its lifeblood. Sports - football, at any rate - has taken over educational institutions and occasionally become the most important thing about them, and now we see what terrible moral havoc that can wreak.

Count to 45.

When an institution like a football team becomes that important and causes this kind of damage, you need to start over. You can't continue to protect the team that these men protected by hiding another's heinous deeds from the world. Start over. Tear it down and start over.

I hope the new leadership at Penn State does the right thing. They'll be booed on the road; I'm terrified of the signs opposing fans will hold up at those games; every football Saturday will be occasion to wonder how Penn State is righting its wrongs (and to talk about the legion of civil suits against PSU that will take years to finish). They should take the high road and pre-empt others' condemnation by condemning themselves and drawing the curtains on the football team. So far? They've decided to keep Paterno's statue up and to remodel the locker rooms that served as the scene of the crimes.

Do better.

If they don't, I hope the NCAA does. The NCAA is a hypocritical, sanctimonious, exploitative farce, but they have to get this one right. They banned USC from the post-season for two years and took away 20 scholarships because the school failed to properly monitor its team. They suspended five players and took scholarships away from Ohio State because its coach lied about the memorabilia his players exchanged for tattoos. Almost 30 years ago they gave Southern Methodist the "death penalty" - two year suspension of the entire football program - because of a scandal involving cash payments to players - and the participation of the school's President and Chairman of the Board of Governors.

The term of art for violations like these? "Loss of institutional control." Is there a more clear cut case of "loss of institutional control" than a school's President, Vice President, AD, and beloved football coach covering up multiple instances of child rape to protect the football program? If "loss of institutional control" doesn't mean that, then it doesn't mean a damn thing.

There isn't going to be an easy way for Penn State to do this. There isn't a way that won't punish some of the innocent students and players. I know the "proper" solution is one on which reasonable people disagree, and maybe you think shutting down the program for a year or two is too harsh. If you do:

Try counting all the way to 45 knowing that each number represents the horrific rape of a child. I bet you don't make it.

Friday, July 13, 2012

Weekly Round-Up for July 13th

If you're looking for more reasons to feel an overwhelming sense of loss and despair, the Freeh Report on Penn State's scandal ought to do it.

If you don't believe me, John Culhane says Penn State could learn from the BP oil spill. That is never a good sign...

The Chronicle of Higher Ed weighs in on the "culture of reverence" that contributed to the harrowing mess.

In fact, here: a link to ALL the Chronicle's coverage on Penn State.

Ta-Nehisi Coates has something to say about it too.

Dahlia Lithwick wonders why liberals don't show the kind of outrage that's been directed at John Roberts when their justices jump the wagon.

And let's not forget that the Court said it won't take another look at Citizens United.

Katy Waldman reminds us that, by the way, it's okay to be "wobbly" every once in a while (again, like John Roberts).

And the leaks from within the Court about the ACA aren't anything new, either.

But while we're wondering, was it Ginni Thomas who blabbed?

When Andrew Leonard's house burned down, the firefighters came, and now he understands why taxes are important. True story.

And the CBO says we aren't being overtaxed, so calm down.

This one is FASCINATING: should people who fly drones from a military base get medals for bravery?

If you don't believe me, John Culhane says Penn State could learn from the BP oil spill. That is never a good sign...

The Chronicle of Higher Ed weighs in on the "culture of reverence" that contributed to the harrowing mess.

In fact, here: a link to ALL the Chronicle's coverage on Penn State.

Ta-Nehisi Coates has something to say about it too.

Dahlia Lithwick wonders why liberals don't show the kind of outrage that's been directed at John Roberts when their justices jump the wagon.

And let's not forget that the Court said it won't take another look at Citizens United.

Katy Waldman reminds us that, by the way, it's okay to be "wobbly" every once in a while (again, like John Roberts).

And the leaks from within the Court about the ACA aren't anything new, either.

But while we're wondering, was it Ginni Thomas who blabbed?

When Andrew Leonard's house burned down, the firefighters came, and now he understands why taxes are important. True story.

And the CBO says we aren't being overtaxed, so calm down.

This one is FASCINATING: should people who fly drones from a military base get medals for bravery?

Monday, July 9, 2012

AA for Effort: This Lawsuit is More Masturbatory Than Most

Rooks has never done a guest post for someone else before, so this was fun, if probably longer than Alex was expecting! This post and other sexytimes law ruminations can be found at Between the Briefs, and she also corrals a herd of awesomeness over at Res Ipsa Etc., where she hopes to get Alex to return the guest post favor sooner rather than later.

Today's moment of deep-seated appreciation for all the delightful readers and content aggregators out there in the series of tubes interwilderness is brought to you by my unceasing delight in waking up to emails of links like the following:

YES! I mean, probably, "Oh no," but I'm still excited, perhaps perversely, about such apt sex law fodder, not to mention someone asking me if I have thoughts - specifically regarding whether the elective nature of the course matters, and on the issue of alternative assignments. Yes, I sure as hell do have the thoughts! Of course I do! Many of them. After all, basically all I do at Between the Briefs is think about sex (ok, and occasionally the law as well).

In brief, for all you TL,DR readers out there, I don't think it constitutes sexual harassment. I can understand how the elective nature of the course might matter in that assessment. And while the refusal of an alternative assignment makes a certain degree of sense to me, I do actually think the assignment itself is odd (though not for the reasons elucidated in the article linked above).

A Short Summation:

Karen Royce, a returning student seeking to become a social worker, took a human sexuality course from Prof. Tom Kubistant, one in which he required the signing of a waiver due to the explicitly sexual subject matter covered during the course on the very first day of class. Basically, the waiver acknowledged that the students in question were aware of the nature and requirements of the class, which is to say they knew what the hell they were getting into, as it were. Royce went ahead and signed her waiver without reading it - rookie mistake, kids! - and then was appalled, appalled, to discover that the professor really did require "his students to masturbate, keep sex journals and write a term paper detailing their sexual histories in order to receive a passing grade." Go fig. Royce simply couldn't believe that a human sexuality course would ask students "to list different types of sex and sexual positions," or that Kubistant would "read the lists aloud to the class and then [ask] the students to write three 250-word journal entries about their sexual thoughts for homework," much less, "assign a 14-page term paper which required students to detail sexual exploration, abuse - including rape - virginity loss, cheating, fetishes and orgasms, among other things." THE HORROR.

Royce dropped the class after four meetings, but she was so generally wigged the hell out and concerned for the poor, poor children - who, by the way, seem to unambiguously support the professor, who's quite popular at the college - that she initiated an investigation at the university, alleging sexual harassment. The investigator reviewed the syllabus and spoke to folks, and found that there were no shenanigans going on. Royce then addressed her concerns to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, who subsequently agreed with the school that there were still no shenanigans going on. Now Royce is appealing her indignation to the U.S. District Court of Nevada, again asserting that Kubistant's assignments invaded her privacy and were tantamount to educationally sanctioned sexual harassment.

But is she right?

Well, no. Sexual harassment in schools is ruled by Office of Civil Rights sexual harassment guidelines under Title IX, not the EEOC guidelines, namely, as my sexformant rightly points out, "Whether the harassment rises to a level that it denies or limits a student's ability to participate in or benefit from the school's program based on sex." So, there's a reasonable amount to parse in that seemingly simple statement. Can the student not participate in the school's program? If not, is this inability based on "sex" as understood under Title IX? The school is clearly aware of the goings-on in Kubistant's class, but the course itself is one of several options to fulfill the degree requirement in question in Royce's case. Not looking great for Royce. If the assignment were sexual harassment, one could certainly argue that it would be illegal in that it's quid pro quo -

Today's moment of deep-seated appreciation for all the delightful readers and content aggregators out there in the series of tubes interwilderness is brought to you by my unceasing delight in waking up to emails of links like the following:

Lawsuit vs. school cites masturbation assignment

YES! I mean, probably, "Oh no," but I'm still excited, perhaps perversely, about such apt sex law fodder, not to mention someone asking me if I have thoughts - specifically regarding whether the elective nature of the course matters, and on the issue of alternative assignments. Yes, I sure as hell do have the thoughts! Of course I do! Many of them. After all, basically all I do at Between the Briefs is think about sex (ok, and occasionally the law as well).

In brief, for all you TL,DR readers out there, I don't think it constitutes sexual harassment. I can understand how the elective nature of the course might matter in that assessment. And while the refusal of an alternative assignment makes a certain degree of sense to me, I do actually think the assignment itself is odd (though not for the reasons elucidated in the article linked above).

A Short Summation:

Karen Royce, a returning student seeking to become a social worker, took a human sexuality course from Prof. Tom Kubistant, one in which he required the signing of a waiver due to the explicitly sexual subject matter covered during the course on the very first day of class. Basically, the waiver acknowledged that the students in question were aware of the nature and requirements of the class, which is to say they knew what the hell they were getting into, as it were. Royce went ahead and signed her waiver without reading it - rookie mistake, kids! - and then was appalled, appalled, to discover that the professor really did require "his students to masturbate, keep sex journals and write a term paper detailing their sexual histories in order to receive a passing grade." Go fig. Royce simply couldn't believe that a human sexuality course would ask students "to list different types of sex and sexual positions," or that Kubistant would "read the lists aloud to the class and then [ask] the students to write three 250-word journal entries about their sexual thoughts for homework," much less, "assign a 14-page term paper which required students to detail sexual exploration, abuse - including rape - virginity loss, cheating, fetishes and orgasms, among other things." THE HORROR.

Royce dropped the class after four meetings, but she was so generally wigged the hell out and concerned for the poor, poor children - who, by the way, seem to unambiguously support the professor, who's quite popular at the college - that she initiated an investigation at the university, alleging sexual harassment. The investigator reviewed the syllabus and spoke to folks, and found that there were no shenanigans going on. Royce then addressed her concerns to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, who subsequently agreed with the school that there were still no shenanigans going on. Now Royce is appealing her indignation to the U.S. District Court of Nevada, again asserting that Kubistant's assignments invaded her privacy and were tantamount to educationally sanctioned sexual harassment.

But is she right?

Well, no. Sexual harassment in schools is ruled by Office of Civil Rights sexual harassment guidelines under Title IX, not the EEOC guidelines, namely, as my sexformant rightly points out, "Whether the harassment rises to a level that it denies or limits a student's ability to participate in or benefit from the school's program based on sex." So, there's a reasonable amount to parse in that seemingly simple statement. Can the student not participate in the school's program? If not, is this inability based on "sex" as understood under Title IX? The school is clearly aware of the goings-on in Kubistant's class, but the course itself is one of several options to fulfill the degree requirement in question in Royce's case. Not looking great for Royce. If the assignment were sexual harassment, one could certainly argue that it would be illegal in that it's quid pro quo -

"The type of harassment traditionally referred to as quid pro quo harassment

occurs if a teacher or other employee conditions an educational

decision or benefit on the student's submission to unwelcome sexual

conduct. Whether the student resists and suffers the threatened harm or

submits and avoids the threatened harm, the student has been treated

differently, or the student's ability to participate in or benefit from

the school's program has been denied or limited, on the basis of sex in

violation of the Title IX regulations."

-

namely, a shitty grade. But clearly OCR doesn't think so, and they are

the folks in charge, dammit. Even if we won't just take their word on

it, the inference that the alleged victim needs to loosen the hell up,

if that's what happened and depending on precisely how it was phrased

and the context of the pedagogical methodology of the course

structure, could possibly rise to that level, but that's a statement,

not the assignment itself. It certainly doesn't seem like such things

were said so frequently re: Royce to meet the requirements of hostile

environment - especially not in what basically amounts to 1-2 weeks

worth of class, depending on the frequency of the meetings, and super

especially if there's a reasonable inference that Royce arguably invited

the reply by publicly commenting on her own masturbation habits first,

after having signed the waiver.

Beyond that, neither the statement nor the assignment constitutes an offensive remark about someone's sex (embodied gender), nor an unwanted advance, request for a sexual favor or other harassment of a sexual bent. Like I said already, I don't

believe that the lack of alternative constitutes severe and pervasive,

which is, I think, the other thing the school is getting at by harping

on the elective nature of the course in the first linked article - it's

certainly not the only elective for that requirement, so it's not

pervasive, and giving someone a failing grade if they refuse to do

required work isn't, in and of itself, severe. (I'll come back to

whether I think the refusal of an alternative is odd.)

Does it matter?

As

a teacher myself, it's perhaps a bit more . . . complicated. I

understand the purpose of the assignments detailed, and frankly, knowing

that Royce wants to be a social worker makes it seem like even more of

a good idea. (The notion of a social worker who's easily offended and

rather a bit judgy about sex is frankly disturbing to me.) The fact

that it's required without alternative assignment can be tough, I

realize, but it's likely for a good cause. I know that, when I was

teaching human sexuality, we required the wee kiddles (ages 17-25, so not actually very wee) to read and watch

what some might call pornography, and occasionally people would ask if

they could do something else instead. That answer was, inevitably,

"no." The point was not to agree with the instructors, but to expose

oneself to and potentially confront ideas and notions one may not have

engaged before, and students don't do that by getting out of anything

that they simply don't care to engage, for whatever reason. That's not

the point of, you know, education.

In order to

ensure a minimum of fuss (similar to this scenario, but without a

written waiver), we would announce at the beginning of the course that

the readings and viewings on the syllabus were required, and if a

student didn't want to participate in them, they could drop the class.

This disclaimer was direct and, though simple in outcome, elaborate (in

some ways) in explanation - we'd go over what was in each of the

potentially problematic assignments and say, "this is what this is

about, these are the sorts of sexual expressions you might read about,

and if you can't handle that, and handle engaging in a respectful

discourse about that, then this isn't the course for you." Seriously,

it was like a dramatic reading of a syllabus. (Very meta.) As such,

and with the caveat of my own background firmly in place, allowing no

alternatives makes complete sense to me, pedagogically. (Additionally,

to be in Title IX compliance, schools must not "treat one student

differently from another in determining whether the student satisfies

any requirement or condition for the provision of any aid, benefit, or

service." So it seems as if an alternative assignment could potentially

get someone in even hotter water.)

Regardless, assigning masturbation, given the academic climate I reference below, not to mention the cultural one, is bold, yo. Beyond an admiration for the professor's pluck, however, I'm not sure

how I feel about a mandated sexual act - like, if the student were

legitimately asexual,

what then? Positioning oneself in an authoritative stance and

subsequently telling someone clearly subordinate within that power

structure - teacher/student - what to do with their body, even if that

thing would likely be a very good idea or at the very least really

rather educational, smacks of the sort of patriarchal control over the

sexuality of others that many scholars frequently find problematic.

Conversely, of course, there's absolutely something to be said for

expanding the discourse on sexual expression at the most basic, personal

level, especially in a class where one must be able to effectively

communicate about sex in fairly public fora in order to grasp and

engage the concepts being discussed. It's a toughie. To my mind, the

better assignment might be to have them document and journal about how

they express or don't express themselves as sexual beings (be it

masturbation, or looking at cute people, or engaging in fetishistic

behavior re: clothing choice, or fucking somebody, etc.), and to

contemplate why that is, to critically engage what that might mean,

rather than instruct them to touch themselves more and write about it,

finis.

The "draw your orgasm" assignment is, in

some ways, just as potentially exclusionary, especially on a college

campus - depending on how it's crafted, it quite possibly invisibilizes anorgasmia,

which has been documented repeatedly as an extremely common phenomena

for younger ciswoman types (I dunno if anyone's done a study on

anorgasmia in young trans populations, but I'd be keen to read it, if

so) though it does also occur in other demographic groups as well. As such, the homework, perhaps inadvertently but nonetheless, creates an

assumption of normality in the ability to orgasm that is frankly

unreasonable given the population stats of college campuses (not to

mention that, in my personal experience, many introductory level human

sexuality courses tend to have predominately woman-identified students).

On the other hand, I think it would be fascinating and potentially

illustrative (pun extremely intended) to have folks draw/describe what

they think orgasms should or do look or feel like, especially if

partnered with some sort of reading about the topic with additional

historical and/or cultural significance - like, say, excerpts from Nancy

Friday or Betty Dodson, perhaps in addition to works with a more

specifically medical bent, like The Science of Orgasm, or The G-spot

(if you wanna go old school and/or historical with it). That could

potentially contextualize the conversation in an intersectional

discussion of how sexual questions tend to span

cultural/social/medical/ethical/moral/historical/legal/political/theoretical

(phew!) fields, dare I say spheres, of influence. Further, a professor

might then explore how our understanding of something as seemingly

concrete and specific as "orgasm" is bound within these particular understandings, yet drawn in these situational nibbles and bites from

all of them, and thus examine the extent to which the study of sex,

whether currently or historically, probably ought to do likewise in

order to even begin to grasp the near-infinite complexity surrounding

what's often thought of as an extremely concrete act. (Actually, should

I ever get to make my own syllabus, I'm totally doing an orgasm week.

Or hell, even beyond that, it would be more than a little awesome to

structure a syllabus on the commonly elucidated stages of arousal and

excitement and whatnot.)

I do think, on a

personal level, as an instructor I might feel a bit . . . odd reading

sexual case studies of my students - in no small part because the

pressure to avoid even a whiff of inappropriate conduct is, in my

observed experience, even higher for those teaching in arguably

transgressive fields. It's sometimes hard to disengage oneself from

that clearly messed up narrative. Naturally, it's possible that anonymous

submission might address that concern (though frankly, with some

students it might not be hard to guess, and that barrier is broken,

potentially, when it's time to input grades).

The presumption that it's

inappropriate, however, is likely more troublesome to me than the

potential, err, inappropriateness of these assignments themselves.

That idea works on the notion that reading about someone else's sex life

must necessarily be prurient, and that's a notion that has been getting

in the way of funding for sexual research and less abashed scholastic

exploration of sexual topics for decades now, not to mention the

perception of the credibility of those who chose to do academic work in

human sexuality in a variety of fields (to wit, the narrative I

mentioned earlier). At least one of the above articles (the NY Daily

News one) falls into precisely this trap, discussing the teacher as if

his assignments are freakishly pervy! Terribly licentious! Filthy, filthy nastiness of epic proportions! Royce's

lawyer encourages these histrionics, stating, "My mind immediately went to the

question is he grooming these young 17-, 18-, 19-year-olds so he can

have further contact with them outside the school environment?" Tell

you what, dude, if that's where you're mind goes first, what I don't want is you teaching kids - I'll gladly roll the dice on the beleaguered and well reviewed professor.

If

we're being honest, though, I think the worst bit of prospectively

reading the sexual history of a student is ridiculously evident - the writing.

Anyone who's read the work of the average college student can tell you

that that business is not infrequently dishearteningly abysmal. I mean

sure, given a deadline and Wikipedia, most of the kids could probably

pop out a particularly porny chapter of Fifty Shades of Grey,

but this is supposed to be a more clinical history, if I'm understanding

the assignment correctly. In my head, it would be like a Harlequin

romance novel had a poorly punctuated one night stand with a particularly dry

chapter of The Kinsey Report, resulting in a painfully mediocre lovechild . . . as written by an undergraduate. Can

you imagine having to read 75-150 fourteen page papers of that? (Plus

the journals and all the rest?) It's positively shudder inducing. I

want to be clear, here - I don't discount the potential interest and

variability of the sex lives of the younger set; I simply don't

have much faith in their ability to cohesively and effectively

communicate same. If anything we should probably thank Kubistant for

taking one for the team, but we'll have to settle for hoping the escalating suits

against him (and the hearteningly supportive administration) come to

naught in the end.

Friday, July 6, 2012

Weekly Round-Up for July 6th

I hope everyone had a great Fourth of July! Be sure to check in again on Monday when Law All Over will have its first guest blogger! But for now, the week's best stories:

Paul Clement had a bad week last week; Emily Bazelon wonders if Supreme Court lawyers are overrated.

Slate presents its reader's best suggestions for revising the Constitution: a very fun and thought-provoking list.

Jeff Shesol continues the conversation about John Roberts.

They certainly don't know it, but I think Dahlia Lithwick and Barry Friedman disagree with my Monday post; they think the politicization of the Court ought to have us worried.

Andrew Koppelman isn't dissecting Roberts either.

Joshua Holland shows that people who claim not to like the ACA actually like the specifics more than they think.

Les Leopold thinks we need to take a long look at Europe's vacation laws.

Paul Campos advances the intriguing argument that Roberts essentially wrote BOTH opinions in the ACA decision.

The Chronicle of Higher Ed reveals that Joe Paterno might have had a pattern of intervening in University disciplinary matters.

Also at the Chronicle, a story about the NJ Supreme Court decision to shield student legal clinics from discovery.

The Atlantic weighs in on the new news about Joe Paterno as well.

Paul Clement had a bad week last week; Emily Bazelon wonders if Supreme Court lawyers are overrated.

Slate presents its reader's best suggestions for revising the Constitution: a very fun and thought-provoking list.

Jeff Shesol continues the conversation about John Roberts.

They certainly don't know it, but I think Dahlia Lithwick and Barry Friedman disagree with my Monday post; they think the politicization of the Court ought to have us worried.

Andrew Koppelman isn't dissecting Roberts either.

Joshua Holland shows that people who claim not to like the ACA actually like the specifics more than they think.

Les Leopold thinks we need to take a long look at Europe's vacation laws.

Paul Campos advances the intriguing argument that Roberts essentially wrote BOTH opinions in the ACA decision.

The Chronicle of Higher Ed reveals that Joe Paterno might have had a pattern of intervening in University disciplinary matters.

Also at the Chronicle, a story about the NJ Supreme Court decision to shield student legal clinics from discovery.

The Atlantic weighs in on the new news about Joe Paterno as well.

Monday, July 2, 2012

Three Reminders from the ACA

Having posted somewhere between 6,000 and 7,000 links about the ACA (estimated), I don't think I need to really wade into the decision. It would be, at best, redundant. So instead, a brief post today on what the ACA decision tells us we ought to keep in mind when we argue about the role of law and courts in our society. It serves as an excellent reminder that as much as we like to think of the high Court as a bastion of justice - at least in our rosier moments - it is a part of our political system, embedded among other political structures and institutions and subject to many of the same pressures and influences. =

The Supreme Court Hears a VERY Select Sub-Set of Cases

It's true that a simple model based on the Justices' political affiliations can predict 75% or so of Supreme Court outcomes. A friend of mine likes to push the obvious conclusion to its logical extreme and say that this amounts to proof that law doesn't mean anything, that political party and politics determine everything, that law is merely the continuation of politics by other means. I often have to remind him that while no one seriously contends that law as a phenomena exists in a world removed from politics, using Supreme Court cases as evidence in this case is a poor set to use. Cases reach the Supreme Court because they represent difficult legal questions; if they were easy cases, the would have been resolved at the District level - or at least in the Circuits. Usually, by the time they reach The Nine, it is because they have difficult constitutional questions, the answers to which reasonable people can disagree upon.

So when we start to complain that the Court is merely playing politics, it would serve us well to remember that the questions before it are hard ones, and ones to which there are multiple justifiable legal answers. We might disagree with an opinion - and it seems to me that a lack of a legal education is no barrier to closely held views on a matter - but we are dealing with legal experts with a variety of legal philosophies that can lead to any number of logical justifiable (if occasionally erroneous) decisions.

SCOTUS Decisions are Always a Mix of Law, Policy, and Politics

Those who watch the Court from an institutional perspective realize that when a legal issue has no clear answer, other considerations will step into the fold. Whether it's a political leaning, a legal preference, or a preferred policy outcome, second order considerations take the limelight when legal considerations don't yield an obvious answer. This isn't necessarily a bad thing. Let's say you're putting together a rec-softball team, and that you have decided that the way you want to determine which of your friends fill the ten spots is by skill as a softball player. What happens if two friends you're thinking about for the last spot are equally good softball players? If the thing you're supposed to use to make these decisions doesn't yield an obvious answer, wouldn't you be justified in using other rubrics? How good are the two friends? How well do they get along with the rest of the team? Which friend is more likely to bring good beer to the games? Even if you've said that the only thing you want to consider is softball ability, other factors may have to be considered. Skill at air guitar, for instance.

By the way, I want no part of your softball team; it sounds like you take it way too seriously.

Judges Care About More than Political Outcomes

But this is not to say that judges faced with difficult legal questions simply plug in their preferred policy position, dress it up in legalese and hand it down. I think that, if nothing else, John Roberts opinion shows us that judges care about more than simply how close an opinion is to their ideal point. A few possibilities:

Judges Care How the Court Looks

I think Roberts clearly cares how the Court looks to the public, and part of this is not overturning an administrations figurehead piece of legislation. I think he knew that overturning the ACA would put the Court not only in a political fight, but at the center of an inter-branch political fight. It is part of the Court's constitutional duty to overturn unconstitutional provisions no matter how popular they are in the other two branches, but when it's as big a piece as the ACA, the presumption is often to uphold and not get too deeply involved in groundbreaking policy. This is partially accomplished by the legal rule of interpretation saying justices ought to use any available interpretation that renders legislation constitutional, but I think it goes beyond this. I think justices care about how the court looks to the public, and in this case I think Roberts thought striking down such a monumental law would make the Court appear as if it were overstepping its boundaries.

Judges Care How They Look

Two quick points on this. One, reading even the first three pages of Roberts' opinion makes it clear that he knows it's a big deal. He knows that this is going to be read widely and discussed endlessly for the coming months and will be destined to be a staple of Con Law classes for a long time. In that spirit, it's a very clear opinion unusually free of legal jargon. It's written for mass consumption, not a narrow class of the legal commentariat. Knowing that one's words were going to be such a big deal would really make one reflect on them, I think, and not just their style. If you were in his chair, wouldn't you care about not appearing to be partisan? Which brings me to a second point: even if you were an absolute partisan hack, you would probably still care about not appearing to be a partisan hack. This in itself would constrain the options open to you as you considered and authored a judicial opinion. The overlap between "legal opinions that look well reasoned enough to escape hackery" and "legal opinions that achieve my political goals" might yield a much smaller set than the second group alone. If the first consideration is important, even that will prevent you from just writing whatever you want (lifetime appointments be damned).

Judges Think They're Doing More than Just Politics

Let's put aside the discussion of whether judges actually are doing anything more than politics in a different guise. I think they are, others disagree, but regardless, it seems clear (to me, anyway) that judges themselves think they are doing something more, something different, something special. Even if they are in the throws of especially rapacious self-deception, the mere delusion would limit the opinions a judge or justice was able to write while maintaining the facade. Again, I think they actually are doing more, but the point is that even if all the "law" stuff is just a self-constructed mask, the mask still matters. Otherwise we would see a lot more opinions that just said "I think this law sucks and I'm chucking it. Tough." There mere fact that judges would feel compelled to find legal cover would limit the kinds of opinions they could author.

At bottom, yes, the Supreme Court is a political institution in which political considerations play a role. No shock here. But as I hope I've at least begun to convince you (if you needed convincing) it's not merely a political institution. A lot more goes on in chambers than raw, pragmatic, policy maneuvering. If nothing else, the ACA decision is a good reminder of why some of those things are.

The Supreme Court Hears a VERY Select Sub-Set of Cases

It's true that a simple model based on the Justices' political affiliations can predict 75% or so of Supreme Court outcomes. A friend of mine likes to push the obvious conclusion to its logical extreme and say that this amounts to proof that law doesn't mean anything, that political party and politics determine everything, that law is merely the continuation of politics by other means. I often have to remind him that while no one seriously contends that law as a phenomena exists in a world removed from politics, using Supreme Court cases as evidence in this case is a poor set to use. Cases reach the Supreme Court because they represent difficult legal questions; if they were easy cases, the would have been resolved at the District level - or at least in the Circuits. Usually, by the time they reach The Nine, it is because they have difficult constitutional questions, the answers to which reasonable people can disagree upon.

So when we start to complain that the Court is merely playing politics, it would serve us well to remember that the questions before it are hard ones, and ones to which there are multiple justifiable legal answers. We might disagree with an opinion - and it seems to me that a lack of a legal education is no barrier to closely held views on a matter - but we are dealing with legal experts with a variety of legal philosophies that can lead to any number of logical justifiable (if occasionally erroneous) decisions.

SCOTUS Decisions are Always a Mix of Law, Policy, and Politics

Those who watch the Court from an institutional perspective realize that when a legal issue has no clear answer, other considerations will step into the fold. Whether it's a political leaning, a legal preference, or a preferred policy outcome, second order considerations take the limelight when legal considerations don't yield an obvious answer. This isn't necessarily a bad thing. Let's say you're putting together a rec-softball team, and that you have decided that the way you want to determine which of your friends fill the ten spots is by skill as a softball player. What happens if two friends you're thinking about for the last spot are equally good softball players? If the thing you're supposed to use to make these decisions doesn't yield an obvious answer, wouldn't you be justified in using other rubrics? How good are the two friends? How well do they get along with the rest of the team? Which friend is more likely to bring good beer to the games? Even if you've said that the only thing you want to consider is softball ability, other factors may have to be considered. Skill at air guitar, for instance.

By the way, I want no part of your softball team; it sounds like you take it way too seriously.

Judges Care About More than Political Outcomes

But this is not to say that judges faced with difficult legal questions simply plug in their preferred policy position, dress it up in legalese and hand it down. I think that, if nothing else, John Roberts opinion shows us that judges care about more than simply how close an opinion is to their ideal point. A few possibilities:

Judges Care How the Court Looks

I think Roberts clearly cares how the Court looks to the public, and part of this is not overturning an administrations figurehead piece of legislation. I think he knew that overturning the ACA would put the Court not only in a political fight, but at the center of an inter-branch political fight. It is part of the Court's constitutional duty to overturn unconstitutional provisions no matter how popular they are in the other two branches, but when it's as big a piece as the ACA, the presumption is often to uphold and not get too deeply involved in groundbreaking policy. This is partially accomplished by the legal rule of interpretation saying justices ought to use any available interpretation that renders legislation constitutional, but I think it goes beyond this. I think justices care about how the court looks to the public, and in this case I think Roberts thought striking down such a monumental law would make the Court appear as if it were overstepping its boundaries.

Judges Care How They Look

Two quick points on this. One, reading even the first three pages of Roberts' opinion makes it clear that he knows it's a big deal. He knows that this is going to be read widely and discussed endlessly for the coming months and will be destined to be a staple of Con Law classes for a long time. In that spirit, it's a very clear opinion unusually free of legal jargon. It's written for mass consumption, not a narrow class of the legal commentariat. Knowing that one's words were going to be such a big deal would really make one reflect on them, I think, and not just their style. If you were in his chair, wouldn't you care about not appearing to be partisan? Which brings me to a second point: even if you were an absolute partisan hack, you would probably still care about not appearing to be a partisan hack. This in itself would constrain the options open to you as you considered and authored a judicial opinion. The overlap between "legal opinions that look well reasoned enough to escape hackery" and "legal opinions that achieve my political goals" might yield a much smaller set than the second group alone. If the first consideration is important, even that will prevent you from just writing whatever you want (lifetime appointments be damned).

Judges Think They're Doing More than Just Politics

Let's put aside the discussion of whether judges actually are doing anything more than politics in a different guise. I think they are, others disagree, but regardless, it seems clear (to me, anyway) that judges themselves think they are doing something more, something different, something special. Even if they are in the throws of especially rapacious self-deception, the mere delusion would limit the opinions a judge or justice was able to write while maintaining the facade. Again, I think they actually are doing more, but the point is that even if all the "law" stuff is just a self-constructed mask, the mask still matters. Otherwise we would see a lot more opinions that just said "I think this law sucks and I'm chucking it. Tough." There mere fact that judges would feel compelled to find legal cover would limit the kinds of opinions they could author.

At bottom, yes, the Supreme Court is a political institution in which political considerations play a role. No shock here. But as I hope I've at least begun to convince you (if you needed convincing) it's not merely a political institution. A lot more goes on in chambers than raw, pragmatic, policy maneuvering. If nothing else, the ACA decision is a good reminder of why some of those things are.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)